Whether it’s vegan meals or larger-than-life paintings, his creations spark conversations

By Ashanti McLaurin and Ervin Dyer

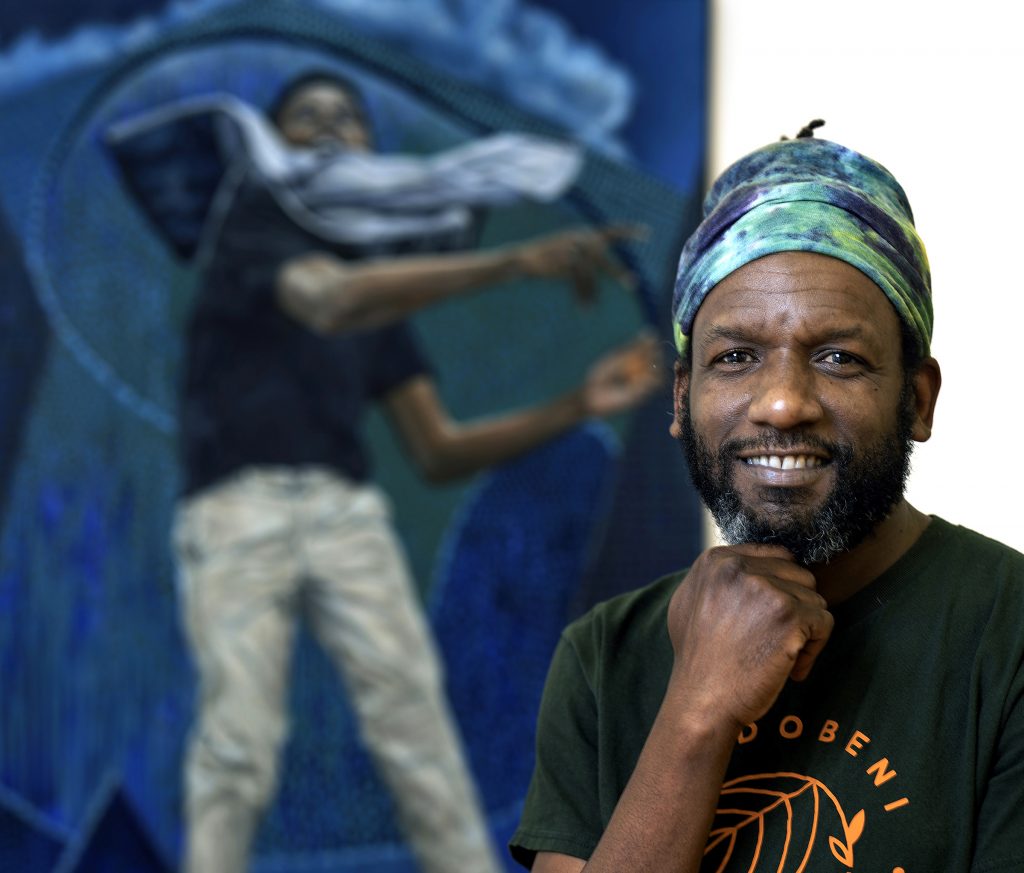

The imprint of growing up in Trinidad and Tobago often shows up in the art and culinary creations of Pittsburgh restaurateur and award-winning painter Ulric Joseph. While his bright oil canvases draw people in, they also make some uncomfortable, as his work stirs up conversations that put a spotlight on racism and injustice. Equally, his vegan eatery is becoming a popular destination for its innovative dishes.

Growing up, Joseph was surrounded by a colorful Caribbean landscape of banana groves and turquoise waters, a colonial past that left the marks of racism on society, and the rhythms of Calypso music embedded with protest and resistance. While at home, he enjoyed his mom’s cooking, which was influenced by centuries of mixing African, European, and East Indian cultures. Joseph witnessed his mother’s creativity expressed as she fed her family and sought to bring beauty into their surroundings.

These influences made him want “to be an artist from as early as I could remember,” says Joseph, now 52. From the time he was eight years old, art was what gave him a sense of freedom, a passion he carried into adulthood. While his artistic desire was supported by his family, he felt pressured to pursue a more traditional occupation like engineering, medicine, or law. Joseph studied and, for a few years, worked in computer science.

However, art kept calling. Due to the limited opportunities for formal training, he searched abroad. His pursuit brought him to the United States in 1995, specifically to Baltimore’s Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA) on full scholarship. He earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts in painting and a master’s in digital arts. For 16 years, Joseph was an adjunct professor and student adviser at his alma mater. During that time, he moved to Pittsburgh, the hometown of his wife, Jennie Canning, who was a teacher in the public school system. He made the four-hour trip to and from Baltimore every few days, commuting for eight years in total.

In the spring of 2015, while Joseph was still connected to MICA, Freddie Gray Jr., a 25-year-old Black man, sustained a traumatic spinal injury while in police custody and died. The tragedy roiled Baltimore and the country.

Joseph wants to pass on the belief to the youth that art is an avenue to transform individuals and communities.

Protests erupted near MICA while Joseph was teaching, and Gray’s death was a rude awakening to the harm and persistence of systemic racism. Joseph was reminded that there is no escape – not even in the art world. The occasional microaggressions he was experiencing made him want to walk away from it all. In one incident, a colleague had shared with someone that he thought Joseph lacked talent and perceived him as a “wild man” when he saw him walk into an art exhibition. At MICA, Joseph was one of less than 10 Black professors on a campus with more than 150 faculty.

In 2019, Joseph finally left MICA, ending his commute and deciding to focus on life in Pittsburgh. In addition to his studio creativity, he is now devoted to working on art projects with youth from underserved communities. He hopes to show the youth that they can create beautiful things and that “they have the ability to dream.” Joseph wants to pass on the belief that art is an avenue to transform individuals and communities.

He began one of his own transformations in 2019, as his art and culinary interests found almost parallel successes. That spring, Joseph created ShadoBeni, a vegan Trinidadian restaurant that began with a series of pop-up locations. It is now based in a sunlit space on Pittsburgh’s North Side. The restaurant is named for culantro, a prickly herb also called chadon beni in Trinidad. The herb is a cousin to cilantro.

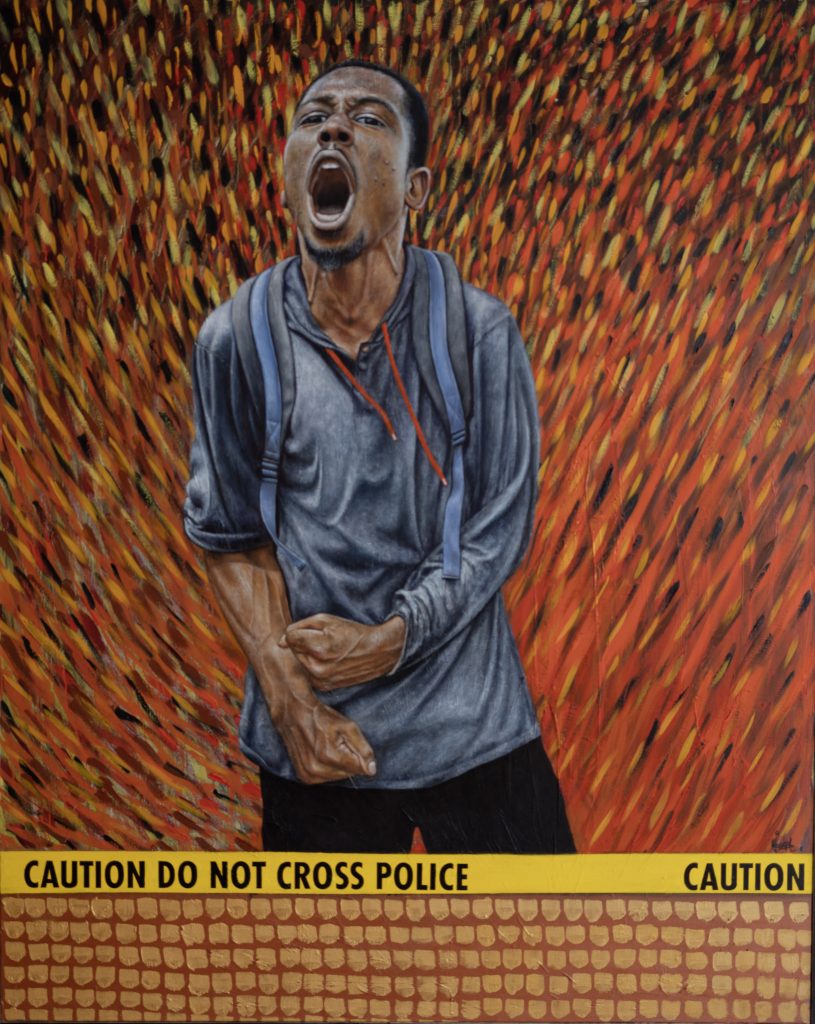

(Left) Joseph’s 6 by 4 foot oil painting “Target Practice.” (top right) Joseph in the kitchen at his vegan Trinidadian restaurant ShadoBeni. (bottom right) Nia, Joseph’s daughter assisting patrons in July 2023 at ShadoBeni on Pittsburgh’s North Side. Photo Credit: Nate Guidry Photography

Influenced by his wife, Joseph became a vegan not too long ago and saw a growing interest in veganism locally. He opened the restaurant to cater to the trend. Sustainability and representation are his priorities. He works with local farmers and small businesses when buying food for the business, which is across the street from a men’s shelter. ShadoBeni donates leftovers to the facility. His vegan meals borrow from his mother’s cooking. Likewise, the Indian-inspired dishes represent his grandfather, other family members, and his roots in Trinidad and Tobago.

As he was starting ShadoBeni, Joseph was also drawing greater attention for his larger-than-life portraits. Since Gray’s death, he has been focused on raising awareness about social issues and opening up conversations on race in America. In June 2019, he won Best of Show in the Juried Visual Art Exhibition at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Arts Festival for his piece, “Target Practice.” It’s a 6-by-4 foot oil painting of a young Black boy with a hoodie over his shoulder and arms pulled back, ready to throw a rock that’s in hand. The piece compels the viewer to wonder if the young teen is the intended target.

Joseph works primarily in oils. After Baltimore, he based many of his creations on photographs from the Freddie Gray protests. While his body of paintings reflect the bright colors and carnival influences of his childhood, their messages shine a critical eye on greed, racism, and stereotyping. His work is also influenced by Mexican muralism, a mosaic style of art that educates and uplifts local heritage and culture.

Joseph credits artists such as Charles White, John Biggers, Carole Alter, Diego Rivera, and Gordon Parks as influences. They have shaped his perspective on how art can be social commentary, particularly its ability to showcase racial pride and question the consequences of white supremacy.

As he looks forward, Joseph is also looking back, inspired to begin painting a series of figures attached to his Caribbean heritage. This includes icons such as “Nanny of the Maroons,” a Jamaican rebel leader during the time of enslavement, and Toussaint L’Ouverture, the leader of the Haitian Revolution.

To date, his favorite piece is “The Scream,” which he created in 2015. It showcases a Black boy screaming with police caution tape in front of him. “Scream” was the first painting that made him step out of his artistic comfort zone. Hearing of the treatment Gray endured and witnessing the lack of consequences against the officers, Joseph wanted to create an image that would make people stop, stare, and think of the injustice Gray and other African Americans face.

“That piece,” he said, “was the turning point in my career.”

Ashanti McLaurin is a writer interested in social justice and Black culture.

Ervin Dyer is a writer who focuses his storytelling on Africana life and culture.