On the heels of her New York Times bestselling book 400 Souls (co-edited with Ibram X. Kendi), public intellectual, 2022 NAACP Image Award Nominee and University of Pittsburgh historian Dr. Keisha N. Blain releases her new book about civil rights legend Fannie Lou Hamer

By Lamont Lilly

The role of the scholar has long been paramount to Black culture and political movements. It is a role that often requires a deep sense of responsibility, commitment, courage, and service—one that professor Keisha Blain personifies.

“I was always interested in learning so I devoured as many books as I could,” says Blain who grew up in Brooklyn, New York. “As a child I would often read to or teach my dolls. I definitely used my voice, as I was very opinionated as a child and perhaps those were early signs that I would one day become a professor.”

An associate professor of 20th century African American History, Blain’s expertise includes race, gender and US politics. The 36-year-old professor arrived on the University of Pittsburgh campus in 2017.

I was excited about the prospect of being in a history department with so many scholars I deeply admire. I loved the department’s focus on transnational history and knew that it would be a good fit for my research and writing.

KEISHA N. BLAIN

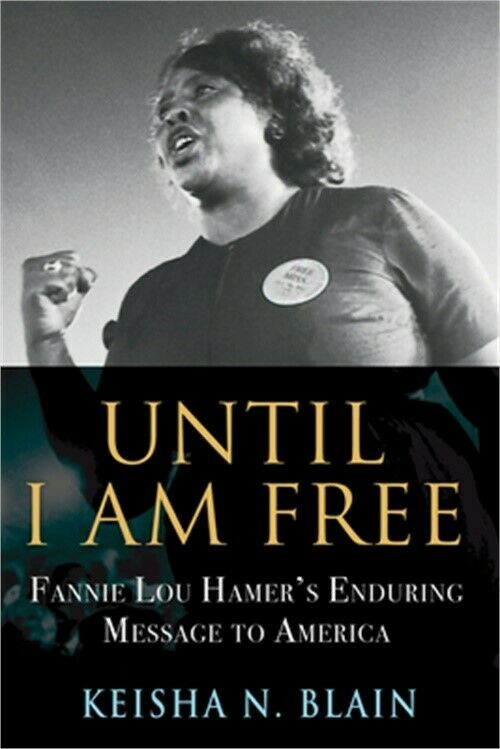

Blain takes her research interest head on with her latest book, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message To America, newly released by Beacon Press. Already nominated for an NAACP Image Award in Literature, the book details Mississippi freedom fighter Fannie Lou Hamer’s life and legacy with a long overdue sense of intellectual care, precision and fierceness.

In the book, Blain explains that Hamer’s grassroots organizing contributions were just as meaningful as the work of Civil Rights icons Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, Dr. Martin Luther King, or Ella Baker. The New York Times Book Review calls Until I Am Free “a much needed history lesson and an indispensable guide for modern activists.”

Until I Am Free not only offers a window into Fannie Lou Hamer’s relentless passion in the pursuit of justice and human rights, it provides readers a clear lens into who Hamer was as a mother, woman, wife, and daughter. For those who are familiar with the Civil Rights Movement and Black Power era, we know Hamer was a fearless and dedicated organizer. What many of us are unaware of, however, is just how candid and uncompromising Hamer was.

For instance, In Chapter 2, “Tell It Like It Is,” Blain details Hamer’s speech to an audience in 1968 at Harvard University: “The wrongs and sickness of this country have been swept under the rug, but I’ve come out from under the rug and I’m going to tell it like it is.”

Until I Am Free both educates and informs. It inspires readers to get engaged in the issues that affect their community, just as Hamer once did. As Blain writes in Chapter 5, “An Expansive Vision of Freedom:” “By linking local and national concerns with global ones, Hamer set a precedent for future generations of Black activists.”

Until I Am Free is just the latest of Blain’s literary contributions. In 2018, Smithsonian Magazine selected Blain’s literary debut, Set the World on Fire: Black Nationalist Women and the Global Struggle for Freedom, as one of the best history books published that year. A year later, the book won the Darlene Clark Hine Award from the Organization of American Historians. She was recently described in Public Books magazine as “one of the most innovative and influential young historians of her generation.”

In February 2021, Blain released the anthology Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019. Co-edited with colleague Dr. Ibram X. Kendi, the book brings together 90 historians, journalists, poets and activists to document 400 years of African American history. Within a week, it landed in the No. 1 spot on The New York Times nonfiction best-seller list.

By detailing the lives of women like Hamer and Henrietta Lacks, or correcting the archives for others such as Eleanor Bumpurs and Laura Kofey, Blain uses her platform to champion the struggles of everyday working-class people, particularly the lives of Black women whose stories are often overlooked, or even worse, omitted.

“When we approach our work from the basic premise that Black women’s ideas and activities are valuable, it transforms our research and writing,” says Blain, whose scholarship consistently offers insight to a new generation of grassroots organizers and activists on the frontline of today’s movements.

In the tragic aftermath of the murderous massacre of nine Black people in a Charleston, South Carolina church by a white supremacist in 2015, Blain and two other professors, Kidada E. Williams and Chad Williams, co-created a grassroots primer, The Charleston Syllabus. The curriculum, which eventually became a book, was birthed via a Twitter thread.

The Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism and Racial Violence offered reflection on the history of racial violence in the U.S. Ultimately, it became a resource guide for activists and scholars alike.

For those looking to the past for solutions to today’s struggles, historians like Blain remind us that Black resistance to oppression and battles for self-determination are nothing new.

“During the Civil Rights-Black Power era, Black activists were at the forefront of challenging police violence and calling attention to the devaluation of Black life,” she says. Just as today.

Photo by Melissa Blackall, courtesy of the Hutchins Center

In addition to teaching and book writing, Blain makes time to write for popular outlets like The Washington Post, The Atlantic and Time magazine. In 2020, she was a W.E.B. DuBois Fellow at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University and this year was named a 2022 New American National Fellow. Blain is also deeply involved in organizations like the African American Intellectual History Society, which she currently leads as president. Her commitments involve much travel and an intense demand of her time.

My family plays a significant role in my life—they keep me grounded. It’s easy to get consumed with work if I’m not careful. I am grateful to have loved ones who remind me to slow down at times and above all, remind me to focus on what’s most important.

KEISHA N. BLAIN

“My family plays a significant role in my life—they keep me grounded,” Blain says. “It’s easy to get consumed with work if I’m not careful. I am grateful to have loved ones who remind me to slow down at times and above all, remind me to focus on what’s most important.”

While Black Pittsburgh may have its challenges with poverty, policing, affordable housing and racial inequality, Blain remains hopeful.

“I love the fierceness, strength and creativity of Black people. We have been through so much—we are still going through so much. But I marvel at how we still manage to create beauty every single day; how we remain resilient even in the face of adversity; and how we stand tall and demand that our voices be heard. That to me is quite remarkable.”

As to what keeps her motivated to do the work she does day in and day out, she credits the ability of her research and writing to change hearts and minds.

“I write books that I want people who look like me to read and be emboldened in the continued fight for liberation. And then I write for everyone, who I believe needs to be part of that fight.”

Lamont Lilly is an independent journalist, poet, activist, and community organizer based in Durham, North Carolina. In 2016, he was the Workers World Party U.S. vice-presidential candidate.