BlackPittsburgh.com takes you on his journey from ‘country boy’ to what activists are calling a ‘modern-day lynching’

By Ervin Dyer and Renee Aldrich

Peter Spencer, a 29-year-old dreamer who looked forward to being a first-time father and opening his own restaurant, died doing what he had always done in life: bringing people together.

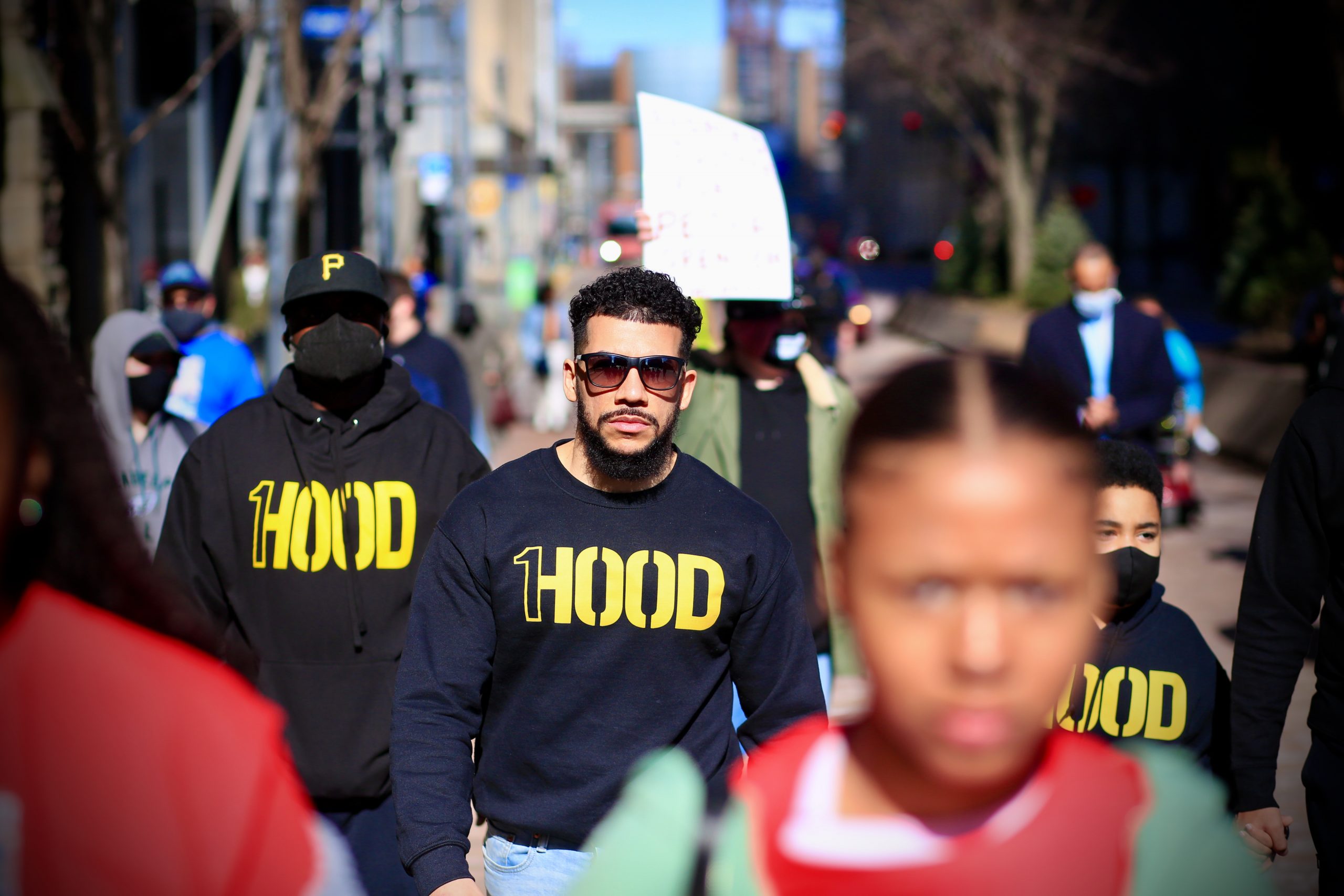

Photo Credit: Ya Momz House, Inc.

Spencer, an immigrant from Jamaica, was killed on December 12 while camping with a former co-worker and three others in rural Venango County, Pa. In the weeks since, international organizations, activists, community leaders, clergy, and social justice advocates have united and called for a more thorough, transparent investigation into the mysterious, perhaps racially motivated, circumstances surrounding Spencer’s death. He was shot nine times, and no one has been arrested in the homicide case.

But who was Peter Spencer and what led him from his neighborhood of Waterhouse, in Kingston, Jamaica, to Pittsburgh’s Highland Park neighborhood, where he had settled to make a new life?

JAMAICAN ROOTS

At its core, Spencer’s journey is a story not much different from the millions of other immigrants who flocked to the Three Rivers for a new beginning.

He was born in Jamaica’s capital, Kingston, the bright and rambunctious son of Conrad and Icilda Spencer. He was the third child in a family of three brothers and a sister.

Spencer grew up in Waterhouse, a colorful, crowded working-class community on the tropical island. It is a neighborhood scattered with dirt yards and tidy cinder-block houses, some of which sit behind walls and barbed wire.

It is an area where gang violence sometimes leaves residents on edge.

But it is also an area where small open-air markets line the streets and where residents hawk clothing and food to make ends meet. Spencer’s mother operated a small business, too. She sold cod and mackerel and chicken and red pea soup every Friday to neighbors, friends, and visitors to Waterhouse. Brick by brick, his father built the family’s home, a friend recalled Spencer saying.

Spencer’s parents brought him up in the Pentecostal church. He sang in the choir. He wasn’t a very good singer, his mother said, but he gave it his all.

Many Black families living in under-resourced communities find themselves knitted closely together, sharing the responsibilities of housing, food, and other costs to survive. It was no different for Spencer’s family.

#JusticeForPeterSpencer March. Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

His younger brother, Tehilah, 27, remembered Spencer as self-taught and multi-skilled, perhaps building upon the carpentry and electrical skills he learned while a student at Jamaica’s St. Andrew Technical High School.

In his family, he was the peacemaker. Spencer didn’t like conflict and was the go-between to settle disputes among his brothers and sisters, said his mom. When someone wanted advice — even his elder siblings — they called on him. If he argued with you at night, he was hugging you first thing in the morning, she said.

Growing up, Spencer considered himself a “country boy” and enjoyed showing off the land to tourists. As a younger man, he worked as a guide, taking pride in ferrying people to rivers and beaches off the beaten path.

Spencer loved nature person and enjoyed laying in the sun. He would walk and hike alone in the mountains. He would take pictures of himself on ledges that seemed impossibly narrow and high. He was so gentle in nature, say friends and family, that he could approach ducks and squirrels in the woods and feed them.

He enjoyed Jamaican food, too, particularly the staples of jerk chicken and meals spiced with curry. Still, he and his family hungered for something beyond the streets of Waterhouse.

Twice that dream put them on a path to the United States.

First, in 2008, at age 16, Spencer migrated to the United States with his father, settling in a small town in North Carolina, where his father became a teacher. The family stayed for less than a year before deciding to move back to Jamaica.

Five years later, a more circuitous route brought Spencer back to the States. His parents divorced and his mother moved to New York City and met and married a Pittsburgh native. When her new husband returned home to Western Pennsylvania, Icilda Spencer-Hunter came with him. In 2013, she filed the proper immigration forms and sent for her son, Peter. He came to live with her in Swissvale before the family moved to Highland Park.

Spencer came seeking no glory or fame; he was simply hoping to build something better than what he had. A deeply spiritual man, he wanted to start again, perhaps reaching for what God had in store for him.

Spencer was 20-years-old when he arrived in Pittsburgh and found work as a janitor and in security for Eastminster Presbyterian Church in East Liberty, not too far from where he lived. He later worked in sales with Verizon and a local energy company. He was successful and enjoyed those positions, said his mother, but he dreamed of something else.

By 2017, he began renting a truck to do independent construction. If he couldn’t do a job, like plastering or tiling, he connected with someone who could and worked hard to learn as he went along. Eventually, he painted, installed drywall, laid carpentry, and did anything in between.

An entrepreneur at heart, Spencer also set his sights on opening a Jamaican restaurant.

“Let’s start something in the house,” his mom recalled him saying a few years ago. To begin, he borrowed his mother’s business model from Jamaica and dedicated every Friday to the project. He soon operated a food cart and a catering business from Highland Park. He had his friends help to deliver food.

Moving to a new country is not always an easy transition, and African diaspora immigrants often have to confront complex issues of ethnicity, identity, and community.

Other barriers include widespread ignorance about the history of different ethnic groups and nationalities and how others define their identities.

Even by speaking English with an accent, African diaspora immigrants can be seen as outsiders. There can be run-ins with the police and with American racism and xenophobia.

According to city of Pittsburgh court documents, Spencer had previously been cited for traffic violations, carrying a loaded weapon without a license, and charges for drug possession and intent to distribute.

“My son was not perfect, but he did not like anyone around him who did not work,” Spencer’s mother told the Gleaner, one of Jamaica’s largest newspapers. Despite the challenges, Spencer seemed to be finding his way.

He grew dreadlocks, and maintained his easy-going manner, easily making friends in his new city. And when he immigrated, Spencer also brought his cultural traditions of unity and mutual aid along.

From his emerging restaurant business, he fed the homeless; he played basketball with neighborhood kids, and sometimes he hired friends if they needed work and provided small loans if they needed cash. Those who knew and loved him described Spencer as being very helpful and praised him for encouraging others to succeed.

LET LOVE RULE

After living in Pittsburgh for about eight years, Spencer met Carmela King, a young nurse, and fell in love. They met in September 2020, in Highland Park, where he was selling Jamaican entrees from his food cart. The two found a connection neither had ever experienced.

“Do you believe in and are you covered by the Holy Spirit?” was one of the first questions he asked King on their first date.

Stunned, King responded that she did believe in the Holy Spirit, and it gave her comfort. No man had ever asked her any such question, nor had one necessarily shown an interest in her spirituality. In that moment, Spencer began to draw her in. He had an intuitive nature that belied his age; he was self-assured and in tune to himself in a way that men in their twenties rarely are, she said.

Spencer also had a heart for others. Their families quickly grew close, and she remembered how her boyfriend would often just sit with her mother, comforting her during some health challenges.

He was a man of broad interests, King said. He enjoyed reading, and “absorbing” books on math and geography. On their dates, he introduced her to outdoor activities like camping, hiking, pitching tents, and exploring for crystals, one of his favorite pastimes.

“There are states that have mines,” she shared. “You go, pay a few dollars, bring your own equipment and dig for things like that.”

Late in 2021, King shared with Spencer that he would become a father sometime in June of 2022. “Peter was very happy and excited,” she said. He began to dote on his fiancée. The couple had spoken about getting married in July, but Spencer wanted to do it sooner and planned a big party celebrating the baby’s birth.

She said Spencer received an invitation to join a former co-worker and his friends for a day of hunting, and as an “outdoorsman,” he was happy for the invite. At 2 p.m. EST, on that day, she drove 90 minutes north of Pittsburgh and dropped him off at a cabin in rural Venango County, where he told her he was to meet the group.

They agreed that she would come back several hours later to pick him up. On her way home, she received a text from Spencer saying, “I’m going to stay here, don’t come back for me. I’ll call you.”

She never heard from him again. Concerned, the next morning she decided to drive back out to where she left him. When she arrived, the cabin and grounds were a crime scene. Spencer was lying on the cabin’s front lawn dead with nine gunshot wounds.

Police said they found multiple guns and drugs at the scene. Police detained and questioned four people, including a 25-year-old white man they called a suspect. But all four were released from custody.

No charges have been filed.

As a nurse who often faces situations that would break others down and as a woman carrying new life, King realized she had to put this tragic situation and the abrupt change in her life in perspective.

“I had a unique love in Peter Spencer,” she says. “While I know I must carry on, I had a pure genuine, crazy love. I will miss his way, his knowledge, being loved by him, and the unadulterated feeling of being genuinely cared for.”

“Peter was a good man,” King continues. “He was filled with love for everyone. He had desires like anyone else, to be successful, to be here, to grow, to become a dad — to be great. Though he was cut down and won’t know the fulfillment of his dreams — at the same time his name is going to be known, not just for what happened to him, but also because of the man he was, who he was trying to become, and the justice his family will get — because his life mattered.”

GROWING SUPPORT

On Sunday, February 6, scores of supporters and friends held a candlelight vigil in a cold and snowy Highland Park to honor the life of Peter Spencer and add their voices to the call for justice.

According to The Washington Post, a former Allegheny County coroner, at the family’s request, examined Spencer’s body and was only able to analyze a few photographs from the funeral director. The former coroner said it appears that Spencer was shot twice in the buttocks, six times in the chest, and once in the mouth (or in the neck), with several bullets entering through his back.

In the weeks since his homicide, questions on exactly what happened have only increased. According to Spencer’s family and Tim Stevens, an activist and the chairman of Pittsburgh’s Black Political Empowerment Project (B-PEP), Spencer’s co-worker admitted to being the shooter and was claiming self-defense. Police have not yet released the man’s name. As of today, no one has been charged in Spencer’s murder.

Many are critical of the lack of transparency in the case.

Attorneys for the family have requested all autopsy photos from the Venango County Coroner’s office and, to date, the request has gone unfulfilled. Authorities have refused to effectively communicate with Spencer’s family regarding the status of the investigation.

“When we ask for updates and more information,” said Spencer-Hunter, “they only tell us they are still investigating.”

For Stevens, this is unacceptable. He’s sent letters demanding a more thorough investigation to the offices of the Venango County District Attorney, the U.S. Attorney General, and the Pennsylvania State Attorney General, asking that Spencer’s homicide be considered a hate crime and an act of domestic terrorism.

We find it impossible to claim self-defense shooting someone twice in the buttocks, six times in the chest, and once in the mouth. This seems to us to be possibly nothing more than a modern-day lynching!

Tim Stevens

In recent weeks, the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Pennsylvania Council of Churches, the Allegheny County Democratic Black Caucus, and Jamaica’s Global Diaspora Council’s Northeastern Region (which includes Pennsylvania) have joined efforts to ensure that justice prevails in this case.

support of his brother. Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

“Our voices will continue to stir and uncover and speak out until we learn what has happened to our brother,” said the Rev. Dr. Larry Picken, executive director of the Pennsylvania Council of Churches. Peter Spencer’s “blood keeps crying out to us.”

Ervin Dyer is a writer who focuses his storytelling on Africana life and culture.

Renee Aldrich is an independent journalist who covers the Black community of Pittsburgh.