Photographer and Filmmaker Emmai Alaquiva wants the Mothers of the Movement to Keep Shining

By Angela Bronner

In the last few years, there has been much talk about trauma in the Black community—collective trauma, familial trauma, individual trauma. So much so, that sometimes it seems like it’s the only story. But a new exhibit at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center, OPTICVOICES: Mama’s Boys, wants us to tap into the other side of trauma—healing, and specifically what healing looks like for the mothers of Black men and boys felled to violence in very high-profile cases.

Pittsburgh-based artist Emmai Alaquiva* opened OPTICVOICES: Mama’s Boys two weeks ago. The interactive exhibit focuses on the joy of 10 mothers (and sons) who have come to been known as “The Mothers of the Movement.”

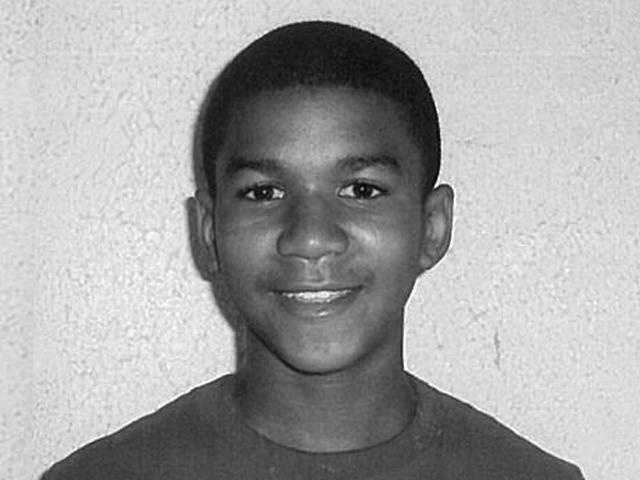

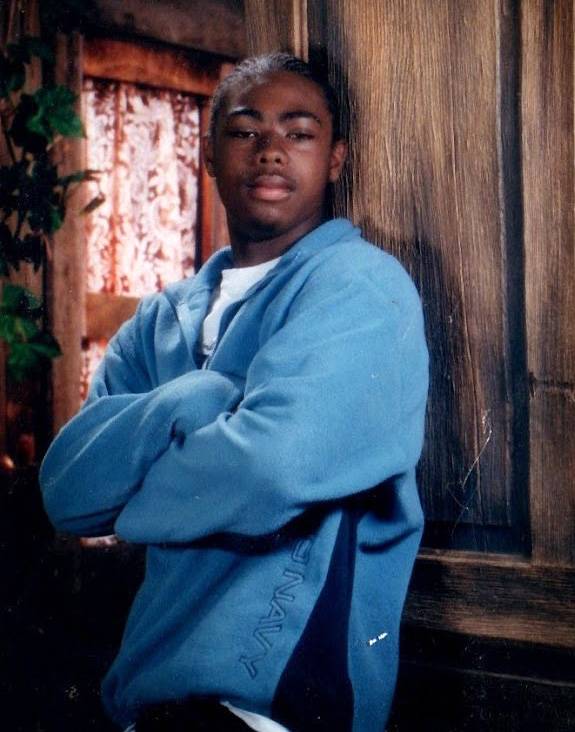

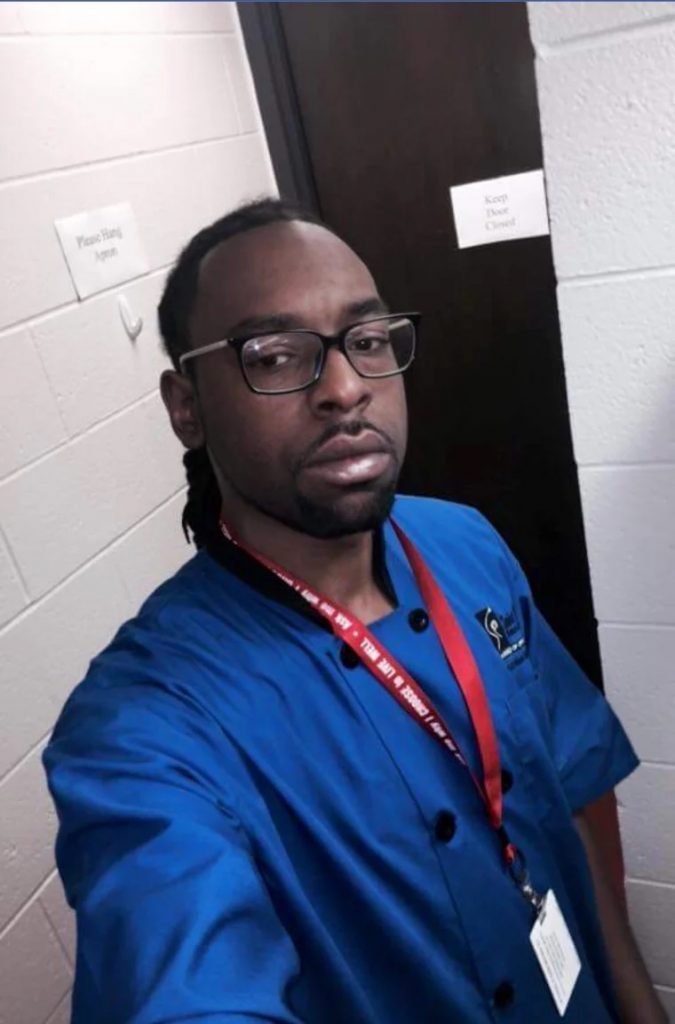

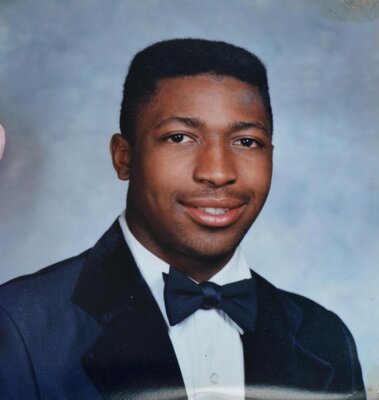

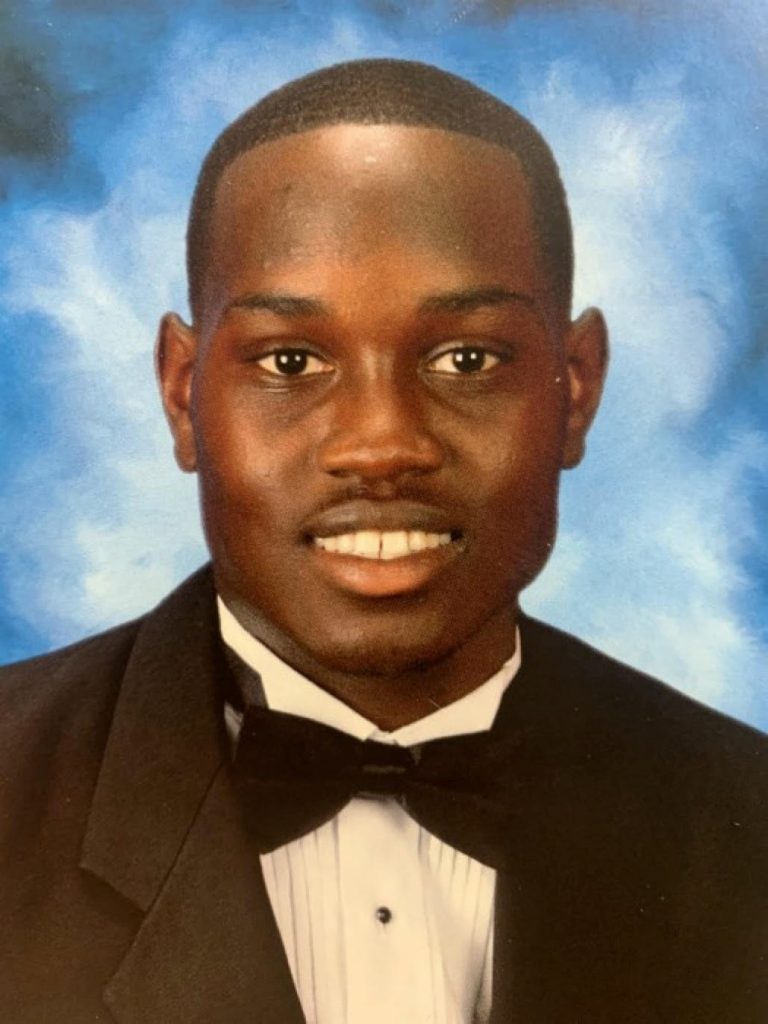

The Sons. Top: Antwon Rose, Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant. Middle: Philando Castille, Mike Brown, Jr., Tamir Rice. Bottom: Eric Garner, Ahmaud Arbery and Botham Jean. Photo Credit: Mothers of the Movement

“As a photographer, being able to take some of these frozen moments, where Sybrina Fulton (mama of Trayvon Martin) smiles at you, and she shows all of her pearly whites, or Valerie Castile (mama of Philando Castile), and she can sit in the middle of the street in Brooklyn and blow you a kiss, this is what healing looks like, even though these mothers may never heal,” says Alaquiva, who received a B.U.I.L.D. (Build, Utilize, Inform, Lead, and Develop) artist residency from the August Wilson Center.

The idea for the exhibit came to him during the pandemic when he witnessed the harrowing death of George Floyd. What struck Alaquiva was that Floyd, in taking his last breaths, called out for his mother.

BlackPittsburgh.com catches up with Alaquiva a few days after the show opened.

How did OPTICVOICES: Mama’s Boys come together?

During the pandemic summer of 2020, hearing George Floyd call for his mama, after she’s been gone for close to a couple of years at that point, really sat with me. To the point where I had to do my thing as an artist to tell the truth about how I felt, but also, answer the question, what can I do to help change the landscape of the world?

Why did you go with the word “Mama” for Mama’s Boys?

I specifically called it Mama’s Boys as a homage to the cultural emotion associated with the term of endearment. I call my own mother “Ma Dukes,” short for Mama.

Are you a mama’s boy?

Yes, I am a mama’s boy. Love my mom to pieces, she’s the savior of my life. I can’t imagine being taken from my mother in that manner, which is why exhibits such as this are so important in carrying on the legacy and beauty of their sons—not the tragedy in which we lost them.

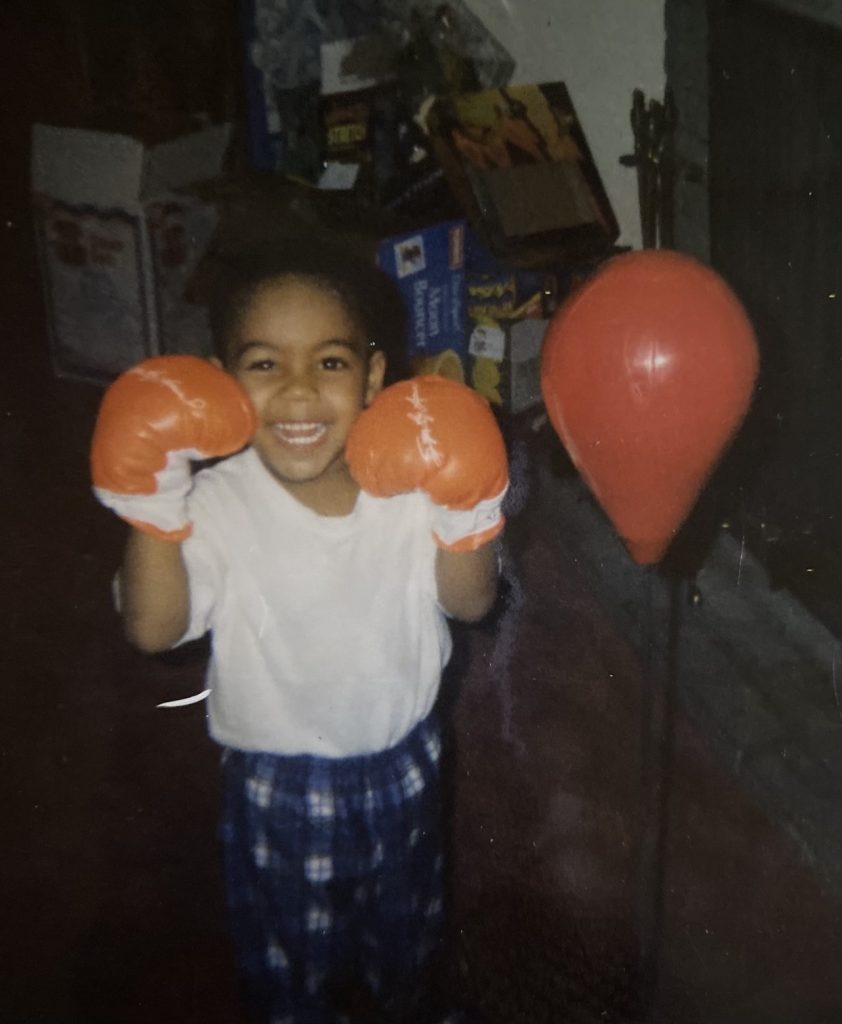

Alaquiva with Samaria Rice (left) and Michelle Kenny (right). Photo Credit: Ya Momz House. This picture of Leon Ford, pictured here at 3 years old. Ford, now an activist, was shot 5 times by Pittsburgh Police in 2012 and survived. His mother, Latonya Green is also featured in the exhibit. Photo Credit: Courtesy of Latonya Green

Why did you focus on healing specifically?

A lot of times, people want to speak about this [type of] work as, they were brutally killed, they were brutally murdered, and this sensationalism that surrounds this subject matter. I didn’t want to focus on the brutal circumstances of the loss, but, instead, what it really means to heal and what does your mental health state look like at that particular moment after a loss. An exhibit like this really helps to focus on that component—and not harp on who did what and how did they do it.

What did you hope to accomplish?

Again, it’s the healing of the moms and focusing on that narration. Often the attention is on “the police BRUTALLY killed…” And I’m just like, ‘hey listen, police aren’t all bad.’ Just like people aren’t all bad. Food isn’t all bad. We can’t do continue to do that. Some of the sons who are in Mama’s Boys weren’t killed by police officers so you can’t lump it all under “police brutality.” And the exhibit is not about that. This is about systemic and senseless violence that, unfortunately, has Black and brown boys and men at the forefront.

Lezley McSpadden, mother of Mike Brown, Jr., shares her thoughts on healing.

What has been the reception so far?

The reception has been outstanding. People understand that this is needed. A lot of educational institutions and nonprofit organizations are setting up tours to come in and check out the exhibit.

Why did you decide to incorporate augmented reality into the exhibit?

I wanted to incorporate augmented reality into OPTICVOICES: Mama’s Boys to provide multiple layers of connection to the audience. Combining the future of technology with the traditional presentation allows for multi-generational intersections of art.

So when you come into the space, you download an app onto your phone. Then take your phone and use the camera in that app. Then you scan, stand back 2 to 3 feet from the actual photo and it transfers from a photo of the mother right in front of you to a baby picture of a son. In another augmented reality component, you scan over the picture of protesters it actually transfers to video footage of that particular march on that day. So the augmented reality jumps at you. It’s almost like having a physical exhibit but also a virtual exhibit all wrapped into one.

Inside the Mama’s Boys exhibit at the August Wilson African American Cultural Center. Photo Credit: Ya Momz House

How about those folks who aren’t so comfortable with technology? Can they still enjoy the exhibit?

Older individuals that might not necessarily want to download an augmented reality app still have the ability to really engage with the work. You can go the website (opticvoices.org) and you can scroll and caption the photo you saw. So it’s also interactive in that way. Or you can do the AR component. Or you could just come and appreciate and get to know educationally what the exhibit has to offer. There’s also a timeline that is educational as well. You can learn about Mamie Till. And next to each of the portraits of the mothers, there are seven facts about each of their sons. So you can discover that Antwon Rose learned to snowboard in Denver, Colorado. You can learn what Philando Castile’s favorite game was on PlayStation. You could learn that Eric Garner could hoop—he was an incredible basketball player. I mean he’d box you out like nobody’s business, right? These were seven facts that I, as an artist, wanted to humanize these men more and more. So that we could not necessarily look at them like they’re savages of society. Because they were human beings at the end of the day.

OPTICVOICES: Mama’s Boys is open through January 31, 2023.’

Angela Bronner is a Harlem-based writer.

* Emmai Alaquiva frequently provides freelance photos for BlackPittsburgh.com