Three years after the state shifted to remote learning, the district is still fighting to course-correct pandemic learning loss.

This story was produced in partnership with the National Association of Black Journalists/Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Black Press Grant Program.

By Melba Newsome

On March 13, 2020, just two days after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, Pennsylvania Governor Tom Wolf ordered the state’s public, charter, private, and parochial schools and its career and technical centers to close for two weeks. On April 9, Wolf revised the order to keep all schools, including Head Start and Pre-K, shut down for the remainder of the 2019-2020 academic year. Every school would revert to remote instruction.

The statewide policy of online learning required all students to have Internet access and a tablet or computer to access the school system. That setup was a serious problem for many of the 21,000 students in the Pittsburgh Public School (PPS) District’s 56 schools where 79.3 percent of students are economically disadvantaged; 51.6% Black, 4.5% Hispanic/Latino and 3.8% Asian or Asian/Pacific Islander.

Science was probably my hardest class because there were a lot of things I couldn’t understand, and I couldn’t directly ask the teacher.

Tranica Byers, Pittsburgh King student

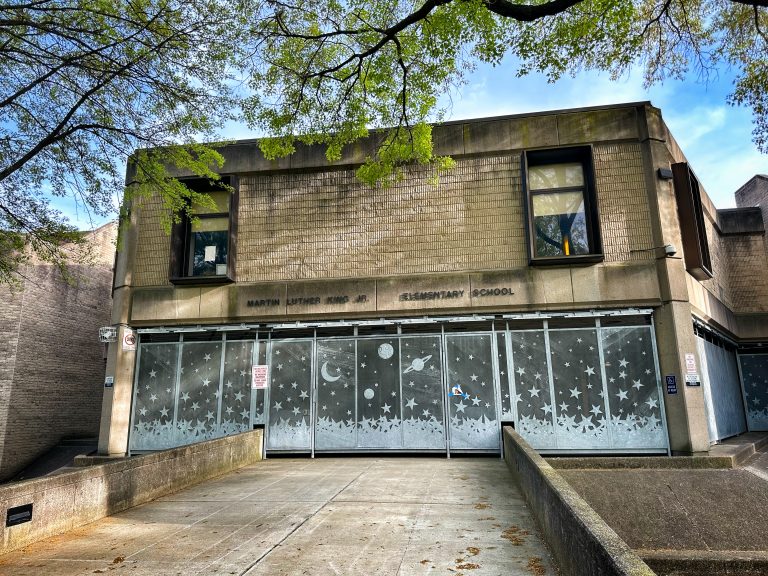

Tranica Byas was a 5th grader at Pittsburgh King, a K-8 neighborhood school on the North Side when schools closed. She and her brother were in a better position than many of the students in the district. They each had computers and her mom was at home during the day and could assist when needed. Nonetheless, remote learning came with significant challenges.

“I didn’t really know how to work anything [on the platform],” says Tranica. “Science was probably my hardest class because there were a lot of things I couldn’t understand, and I couldn’t directly ask the teacher.”

Remote learning officially started for high school seniors on April 16, 2020, and by April 22, students in all grades were receiving lessons. Unofficially, many students lacked Internet access and/or the requisite devices to get online. The school district struggled to provide them.

“Our children in Pittsburgh were not having the benefit of even remote learning for six weeks,” says Tracey Reed Armant, a member of the PPS board of directors. “They were putting together packets because the kids didn’t have computers. There was virtually nothing for our kids to do. It was just a mess.”

By mid-April, PPS ordered 5,000 laptops to augment its supply of 2,500 and received a donation of 599 laptops from the University of Pittsburgh. Nonetheless, the long delay led to growing frustration and anger among students and their families. It also prompted education advocates like Armant and more than 50 other women to form Black Women for Better Schools (BWBS), a coalition of parents, current and retired educators, and concerned community members committed to ensuring high-quality education for Pittsburgh’s Black children. BWBS represented just one of the grassroots efforts to make the playing field more equitable.

These issues were just exacerbated for Black children and families because in this country, anytime something happens, we feel the brunt of it.

Allyce Pinchback-Johnson, co-founder, Black Women for Better Schools

The odds have long been stacked against Black students in PPS. In 1992, Advocates for African American Students in the Pittsburgh Public Schools filed a lawsuit alleging that the school district failed to provide a quality education for Black students. The group cited inequities, lack of opportunities and claimed that Black students were subjected to excessive suspensions and harsher discipline than their white counterparts. The lawsuit also claimed that these inequities created a large academic achievement gap and the subsequent exclusion of Black students from special academic programs.

The case was finally settled in 2005. The school board accepted an agreement with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission that would monitor the district’s progress in increasing the number of Black students in the gifted program and decreasing the number who are suspended.

Thirty years after the suit was initiated and 17 years after it was settled, the disparities for Black students not only persist, but have been significantly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. In February 2021, Pittsburgh City Council members Ricky Burgess and Daniel Lavelle said that the pandemic and systemic racism combined to put PPS in a state of educational emergency.

The Toll of Virtual Learning

The nation as a whole was unprepared for the pandemic and very few organizations and entities, particularly schools, were able to pivot quickly to adjust to the new reality. But Armant says that PPS’ ineptness stood out when compared to other districts in the area. For example, Elizabeth Forward School District has fewer than 2,300 students with only a 10 percent minority population. Elizabeth Forward is also a wealthier 1:1 district (meaning every student in the district has had a computer or tablet for the past decade – unlike PPS).

“They were all able to start remote instruction before PPS,” says Armant. “Those kids went home on Friday and started virtual learning on Monday. So they were able to connect and do work without interruption.”

While comparing a large, majority-minority, under-resourced district with a wealthier white one might not be a fair assessment, BWBS also looked at large districts around the country with similar economics and demographics. Pittsburgh still came up short when compared to Chicago, Baltimore and New York City.

“When you think about the size and complexity of a system, there were obviously some things that other school systems had that our district did not and we weren’t able to move quickly on behalf of our kids. We were sure that part of the problem was district leadership,” said Armant.

Many Allegheny County districts resumed in-person or hybrid learning in the fall of 2020 but the county’s large numbers of COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations prompted the PPS school board to delay school opening. They initially decided to operate remotely only for the first nine weeks, but later determined to continue online learning for the entire school year. “There are no right answers, there are no wrong answers,” said PPS Board Member Kevin Carter at the time. “It’s trial and error at this point.”

As the school year progressed, educators and staff struggled to transfer classes online and keep students interested and engaged. According to a report presented to the board by Theodore Dwyer, the Districts’ Chief of Data, Research, Evaluation, Accountability and Assessments, the time students spent learning remotely diminished significantly as the semester went on. In the fall of 2020, just 57.8 percent of students logged into one of the platforms the district used for remote learning. In total, 127 students did not participate in remote learning; they and their families simply dropped off the map and could not be reached for months.

None of this comes as a surprise to Doreen Upshaw, therapist and CEO of the North Side’s Compass Counseling and Support Services. Upshaw has closely monitored the results of the Adverse Childhood Experience Study to track stressful and traumatic experiences but has never seen anything like the unprecedented stress levels of 2020.

“These numbers really went up in our underserved communities in Pittsburgh Public Schools,” she said.

Upshaw’s clientele is 75-80 percent Black and brown and ranges in age from 4 to 74. During the pandemic, the percentage of students she counseled dropped from 60 percent to 10-20 percent because they could no longer come into her office for therapy.

She held video counseling sessions with some of the K-12 students who were struggling emotionally and were disengaged from their classes. “I saw a lot of depression and anxiety in the kids mainly because they couldn’t go to school or see their friends,” said Upshaw. “They would lay in the bed with very little light and wouldn’t even let me see their faces. And this was during the hours that they were supposed to be in school. Parents were just at their wit’s end as to what to do. It took several sessions for me to convince them to open a window [to let light in].”

A variety of studies found that nearly all students lost educational ground to some degree but learning loss tended to be greater in districts that continued with remote learning the longest. Researchers from the Center for Education Policy Research at Harvard University (CEPR) found that students who attended in-person school for nearly all of 2020-21 lost about 20 percent of math learning during the two-year window. But students who stayed home for most of the school year like PPS, lost the equivalent of about 50 percent, primarily because the district struggled to get laptops to all kids.

That prompted Upshaw to find another way to reach the students. Last summer, she launched CCSS-Mobile, a van equipped as a mobile therapy center to help bridge the gap for students ages 4 to 12 suffering isolation and loss using art therapy, play therapy and other techniques. She meets students at their homes, after school programs or wherever they are comfortable, while continuing counseling for other ages at her facility.

Unfinished Learning

Such huge disparities in the data are really related to issues of poverty and resources.

James Fogarty, Executive Director of A+ school

● National Assessment for Educational Progress tests from 2020 to 2022 found that the pandemic eroded gains made over two decades in national reading and math test scores among elementary students. Math scores declined for the first time ever and reading scores reverted to levels last seen in 1990.

● Harvard’s Center for Education Policy Research found that students in districts that returned to in-person classes relatively quickly lost the equivalent of 10 weeks of instruction. Students in low-poverty districts lost 13 weeks of instruction compared to students in high-poverty districts that lost the equivalent of 22 weeks. National and local assessments showed that the pandemic widened the achievement gap and increased educational inequities for marginalized groups.

● Data from the Northwest Evaluation Association (NWEA), a national educational services organization, shows that when the 2021-22 school year began, students were 9-11 percentage points behind in math and 3-7 percentage points behind in reading.

“These issues were just exacerbated for Black children and families because in this country, anytime something happens, we feel the brunt of it,” said BWBS founding member Allyce Pinchback-Johnson.

National and local education assessments also showed that the more time students who were poor, minority and English language learners spent in online schooling, the further behind they fell, leading to even greater educational inequities. For example, many were expected to provide childcare and assist younger siblings with their schoolwork. Others were uncomfortable with their peers seeing the conditions in which they lived. Additionally, unreliable internet access created constant interruptions.

James Fogarty is Executive Director of A+ school, a nonprofit that supports high-quality educational opportunities for Pittsburgh area students, especially Black and brown children. According to Fogarty, even the schools that showed some of the highest proficiency rates in all subjects had significant performance gaps between Black and white students. “Such huge disparities in the data are really related to issues of poverty and resources,” said Fogarty.

Efforts to Right the Ship

During the summer of 2020, PPS unveiled a number of measures to address the learning loss compounded by a year of remote instruction, including Summer B.O.O.S.T, a modified version of a long-running summer program for K-11 students. The district believed it would be a great opportunity to close the learning gaps that were already emerging, especially for elementary students who were in synchronous online instruction for the first time.

“We prioritized students who we knew needed that in-person, intense instruction the most – students with exceptionalities, English language learners, and young learners who had essentially done kindergarten on the computer,” says Christine Cray, PPS Director of Student Services Reforms.

The program was staffed by 122 PPS personnel, including counselors, nurses, paraprofessionals and physical and occupational therapists. The daily schedule included 90-minute blocks of math and English language arts and also included time for social and emotional learning activities.

Byas applied to Summer B.O.O.S.T as soon as she heard about the program. “I wanted to do it because I really wasn’t doing anything that summer and I was going to be bored,” she says. She believed the program would keep her from falling behind in her studies, particularly English, and also allow her to engage with peers face-to-face, something missing from the online learning module.

In the summer of 2021, the district added a social learning block to Summer B.O.O.S.T and provided resources for students and staff to connect with one another in person because they had been in isolation for extended periods. “There were a lot of challenges, a lot of successes, a lot of lessons learned,” says Cray. PPS also plans to continue the summer learning program for 2023 with a 24-day program that will include an aggressive curriculum and an array of enrichment activities.

When PPS returned to in-person learning during the fall 2022 semester, school leaders knew educators, staff and students would face some challenges but believed they were prepared. However, they later admitted to underestimating the hurdles the district would face in a return to normal.

The district was plagued by a variety of problems. Staffing was so short at some schools that the district had to depend on teachers, bus drivers, cafeteria workers and other staff just to keep the buildings operating. Still, about two dozen schools had to return to virtual learning for days at a time. The district attributed the shortages to an increase in the number of COVID cases.

Counselors and social workers were overwhelmed by discipline problems as students struggled to cope with trauma, fights in schools, and loss. “There was so much going on. It was hard to tease out exactly how those factors played out [for PPS students],” says Cray. “There was also the issue of police brutality and representation of all that trauma and news like the Antwon Rose case.”

Chronic absenteeism was also a problem. In total, 42 percent of students missed so much school they risked falling behind and about half of high school students missed more than 10 percent of school time. COVID-19 restrictions stifled developmental growth. Students had trouble interacting, separating from their parents and transitioning to the next grade levels because they missed the chance to mature alongside their peers and prepare to advance.

We prioritized students who we knew needed that in-person, intense instruction the most – students with exceptionalities, English language learners, and young learners who had essentially done kindergarten on the computer.

Christine Cray, PPS Director of Student Services Reforms

Tranica acknowledges that she struggled socially when the district fully resumed in-person school last fall. “It took a while for me to get back used to things. It took like a month-and-a-half for me to talk to my friends again,” she says. “It helped that our teachers were always telling us to get in groups for homework and stuff, so we had to talk to each other.”

But many of the issues that students were trying to cope with were well beyond the skills of the teachers who were there to guide them. They were also struggling. “Even the ability for teachers who are also parents to show up and think about learning to know that they have children of their own was a problem,” says Pinchback-Johnson. “Some of them who were trying to help navigate online school and the other things that were happening during COVID were also at a loss.”

Looking Ahead

BWBS has used its authority and the opportunity presented by the pandemic to expand its activism into creating systemic, wholesale change within the school district. “We have to create schools that are places people want to be in and are fundamentally useful for kids and families,” says Armant.

The group signed a letter to the school board recommending that the district not renew the contract for Pittsburgh Public Schools Superintendent Anthony Hamlet. They believe that Hamlet’s COVID-19 response was a failure and caused irreparable harm to the district’s Black students. On September 8, 2021, Hamlet resigned, effective less than a month later. Dr. Wayne N. Walters served as interim Superintendent and assumed the top leadership post on August 1, 2022.

But the problems in PPS that were heightened by the approaches to learning during the COVID-19 pandemic will likely persist for years to come. More than 200,000 US children lost a parent or custodial grandparent or caregiver to COVID-19 between April 1, 2020, and June 30, 2021, according to a study published in the journal Pediatrics. And despite the nation’s COVID fatigue, the virus persists. One million Americans died between the start of the pandemic and May 2022. And according to the Centers for Disease Control, by April 1, 2023, the number of US deaths topped 1,125,000. Many were caretakers to the nation’s school children. The impact of these losses deserves greater examination.

Melba Newsome is an award-winning freelance journalist who frequently writes about health, education and social justice.