Did race play a part in sentences for protesters charged with federal crimes during Pittsburgh’s George Floyd Protest?

By Sean Campbell

More than three thousand people gathered in downtown Pittsburgh on May 30, 2020, for a peaceful protest in honor of George Floyd Jr., the man murdered by Minneapolis police that set off nationwide uprisings. But Brian Bartels, a young white man from the city’s suburbs, didn’t seem interested in peacefully protesting that day.

He was dressed in black, and wearing gear from a militant, left-wing animal rights group. He brought a backpack loaded up with rocks and spray paint. The bottom half of his face was covered with a bandana emblazoned with an anarchist’s “A” formed by two assault rifles.

As the Floyd march moved through downtown, past the city’s hockey arena, Bartels got to work on a parked police SUV. He spray-painted an “A” on the hood, then stomped on it. He smashed the windshield and threw rocks at the widows. As a crowd gathered around him, some demanded he stop. One person yelled, “You’re not helping!” Undeterred, Bartels turned and threw up two middle fingers.

The crowd became riled up. A person recording the incident screamed, “This man just busted up this cop car, and you say we are the rioters! You say we are the problem! It is white people!” Another white man threw a skateboard at the car, and others rushed the vehicle. As the crowd surrounded the police cruiser, with multiple people taking part in the vandalism, Bartels briefly celebrated on the hood with another person, then fled. Eventually, the SUV was set ablaze. Court documents and interviews with over a dozen people who participated in the protest say the burning vehicle became the spark for a riot that lasted into the early evening.

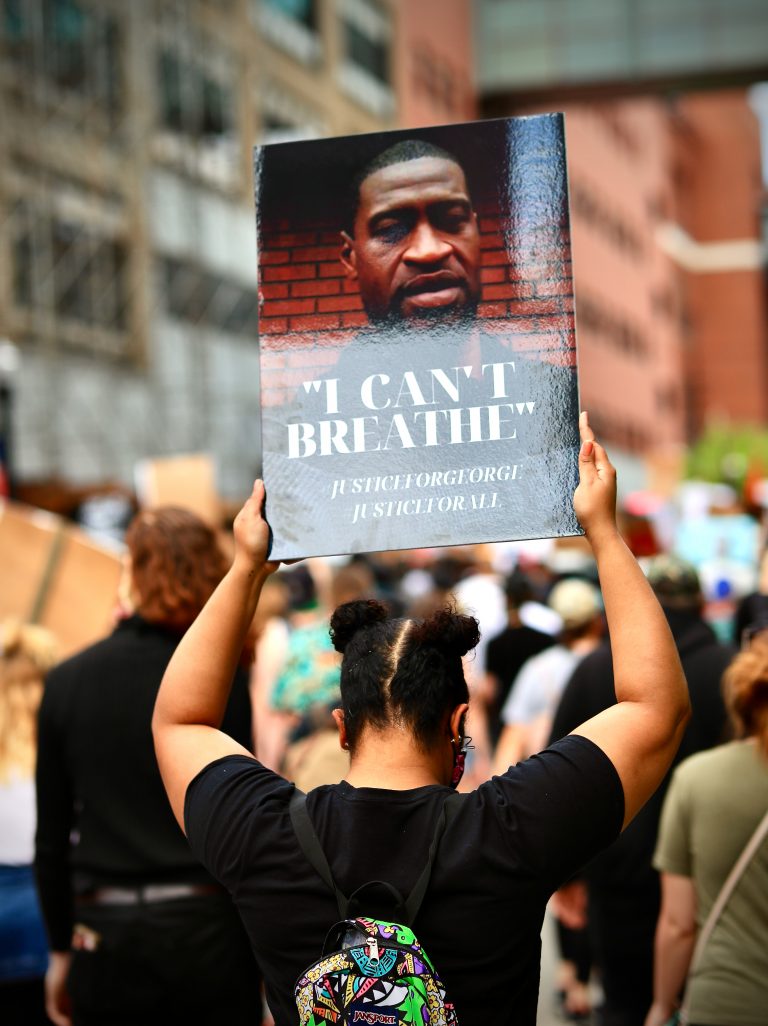

The Pittsburgh George Floyd Protest was peaceful before Brian Bartels’ attack on a vacant police vehicle. Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva.

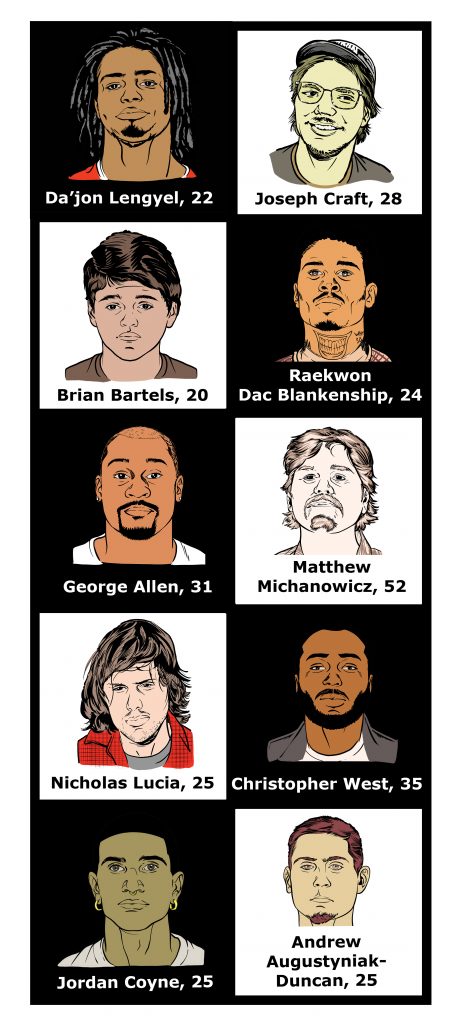

After he was identified through videos, local police and federal authorities found firearms and evidence in Bartels’ home linking him to the violence. Bartels turned himself in and eventually pleaded guilty to his crime–a federal charge of obstruction of law enforcement during civil disorder. He was sentenced to a day of detention and six months in a halfway house. Three Black men also identified in the incident were sentenced to multiple years.

Pittsburgh is one of the top cities in America where federal law was applied to civil disobedience during the George Floyd protests. At least ten defendants have received a federal sentence after pleading guilty so far. Of these, white defendants were sentenced to less time in prison than the Black defendants, even though their actions were arguably more violent, and prosecutors initially requested harsher penalties. This includes another young white man who vandalized two cop cars and threw pepper canisters at police officers who were only sentenced to a day, and a middle-aged white man who received a sentence of time served after he planted homemade explosives near the PNC skyscraper downtown.

The small number of cases, and nuances of each incident, make it impossible to draw definitive conclusions on bias, but legal experts say these cases highlight known racial disparities in Pittsburgh’s criminal justice system. The sentences may also suggest that the court has been more lenient on white defendants.

After reviewing some of the details of these cases, Jerry Dickinson, a specialist in constitutional law and civil rights at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law said, “When you see such glaring disparities, one has to question whether or not the justice system is working the way that we would expect it to work.”

GEORGE FLOYD No Justice No Peace: Highlights from the peaceful protesters on May 30, 2020. Video by Emmai Alaquiva.

Dickinson marched with the protesters before the situation turned violent. He witnessed Bartels’ attack on the unoccupied police vehicle. “It was the catalyst for continued destruction of property and violent activity by numerous people,” he said. Knowing this, he would have expected those who followed Bartels’ lead to be given similar or less time.

Bartels was sentenced in January of 2021. As the first of the 10, the outcome of his case was referenced during the court proceedings of the Black men seeking leniency. But it appears his day in custody had little effect on getting their sentences substantially lowered.

Experts were also concerned that these outcomes would have a chilling effect on people with skin in the game looking to exercise their constitutional right to protest for social justice.

“You have those who are protesting a legal system that they believe is unjust, and then as a result of engaging in that activity–by the way, which is freedom of expression, freedom of speech,” Dickinson said, “and they are met with the full force of a government system that in many ways operates within this realm of injustice.”

Peaceful Protest Turns to Mayhem

The atmosphere of the May 2020 protest was tense from the start. Stay-at-home orders from the pandemic were just beginning to lift across Pennsylvania, and participants told me that it was clear that numerous people were uneasy being in such a large crowd. But Floyd’s murder rekindled the pain of many who had had negative interactions with the police, and they felt compelled to take action.

City’s arrest data show large racial disparities in enforcement. Nearly two-thirds of the people arrested are Black, even though they account for less than a quarter of the city. The Allegheny County Jail is worse. There, 66% of the incarcerated population is Black, even though the estimated county population is around 13% Black. And according to the Pittsburgh

Bureau of Police’s 2021 annual statistical report, almost 70% of all use of force incidents involved a Black person. In the eight self-reported incidents where a police officer fired a gun, the suspects were Black. And the three situations where the suspects died, again, they were all Black.

It was chaotic. It was really scary not knowing which angle violence was coming from.

Brandi Fisher, President & CEO of the advocacy group Alliance for Police Accountability

David Harris is a professor and expert on law enforcement and race at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law. He’s worked with the city’s policymakers for over a decade, and in 2020 he served on the Mayor’s Taskforce on Police Reform. He told me that police enforcement on low-level offenses has been declining since 2015, but at the same time, the enforcement of communities of color has become increasingly disproportionate.

“They’re more likely to actually have records than rights,” he said, of the people living in Pittsburgh’s Black communities. “The least that a city owes its citizens is to get this right, to protect them and to give them the kind of service that everybody expects.”

Multiple people told me the downtown Floyd action reminded them of the protests for Antwon Rose II, an unarmed Black teenager who was shot and killed by a white East Pittsburgh police officer in the summer of 2018. The energy this time was tinged with pandemic awkwardness, but people were excited to support the cause. Some described the march through downtown as peaceful to the point of being uneventful. But that changed once the crowd reached the PPG Paints Arena.

As the crowd walked up toward the Lower Hill District, the previously tight march began to break apart. Bartels started destroying the police cruiser, and others soon joined in, kicking the doors and smashing the windows. After Bartels fled, mounted police rode in to push back the crowd and protect the cop car. The crowd didn’t back down. People threw water bottles and debris. In one video, a Black man, later identified as Raekwon Dac Blankenship, pokes a makeshift sign with “SLOW” on one side and “STOP” on the other at one of the horses.

Realizing the SUV was lost, the mounted units rode off, and the crowd became electrified with their achievement. They swarmed the vehicle and began beating it with skateboards, bats, and whatever else they had on hand. Others jumped on the hood and roof. Among them were the Black men Da’Jon Lengyel and Christopher West. Once a white person lit a fire inside, Lengyel and West threw on paper, cardboard, and other kindling.

A peaceful protest turned violent: (left) an unmarked police car on fire outside PPG Paints Arena, (center) the police SUV burning on Centre Ave., (right) an American flag smoldering at the corner of 6th Avenue and Smithfield streets. Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva.

The crowd’s anger and energy had transformed into a riot. Soon after the police vehicle went up in flames, another unoccupied police cruiser was vandalized and set ablaze. Protesters threw rocks. Police launched pepper spray canisters.

Joseph Craft, a white man from Pittsburgh’s Lawrenceville neighborhood, used a skateboard to break the driver’s side window of the police car before it began to burn. Before that, he twice struck an additional police vehicle that drove past him with the skateboard and later threw pepper spray canisters back at officers. A white man named Andrew Augustyniak-Duncan threw concrete and a metal pipe at officers who would later be hospitalized with concussions. Nicholas Lucia, a white man from New Jersey, threw a small explosive on an officer that was quickly pulled off and thrown to the ground by another officer before it blew up. Police would later say the explosion gave an officer a concussion.

Mounted police and cop cars rode through the streets, some officers directly engaging with the protesters. George Allen, a Black man from the West End of Pittsburgh, threw a piece of cinder block at a police vehicle as it drove away, breaking a window and causing a minor bruise to the officer’s arm.

“It was chaotic,” said Brandi Fisher, President & CEO of the advocacy group Alliance for Police Accountability. “It was really scary not knowing which angle violence was coming from.”

The violent disturbance spread through downtown and lasted until the early evening. By its end, at least three journalists had been attacked, and 60 businesses and other properties reported looting or other damage, according to Pittsburgh Public Safety officials.

Bartels turned himself into police two days later, after numerous people sent in tips identifying him as the catalyst for the destruction, according to an affidavit from an FBI agent in Pittsburgh’s Joint Terrorism Task Force. The court statement says Bartels considered himself far-left and that he was tired of police mistreatment of citizens. He hoped things would change with voting, but they didn’t. His reasoning for the destruction was that it was “a ‘fuck it’ moment for him.”

A month after his indictment, seven others were brought up on federal charges, with at least four more to follow.

The Sentences

The vast majority of federal convictions–97%–come by way of a guilty plea rather than a trial. The protest cases in Pittsburgh are no different. Each of the ten sentences so far came after guilty pleas.

As a result of vast disparities that stemmed from virtually unlimited discretion by the court, Congress passed the Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 that grounded the process in a system of guidelines to determine punishment. The lengths calculated by the guidelines are not mandatory, but they are meant to provide an objective hedge against potential bias. But no two cases are exactly alike, so the facts of each case, a defendant’s criminal history, and other factors are used to calculate the appropriate sentence time. The judge also considers any arguments by the prosecution and defense and recommendations from a probation officer before deciding an applicable guideline range.

Prosecutors argued for the six white defendants to receive an average initial minimum federal sentence of nearly 24 months based on the nature of their crimes and past criminal history. For the four Black defendants, the federal lawyers suggested an average minimum of 22.25 months. But once the judgments were delivered, the white defendants got seven months less than their suggested minimum, on average, while Black defendants averaged the minimum sentence. For the purposes of this analysis, the Black man who was in jail for over a year and given two and a half to five years in state court factored into the average as zero months since that was his federal sentence. Two cases involved in a bank burglary charge that is set to go to trial were not included.

In Bartels’ case, the prosecution and the United States Probation Office argued for a guideline that would result in a sentencing range of 10-16 months. His defense believed 0-6 months was more appropriate. Bartels did not have a criminal history, and after considering what was presented to him, Judge Arthur J. Schwab decided the lower range was correct.

Schwab has had a colorful judicial history. The 76-year-old George W. Bush appointee presided over a 2003 case against Tommy Chong, of Cheech and Chong fame, where he sentenced the comedian to nine months in federal prison for selling bongs. In 2008, Schwab was removed from a public corruption case against a former Allegheny County coroner, and he was rated as the worst federal judge in an Allegheny County Bar Association survey. Three years later, he recused himself from 17 cases where he was accused of bias. Within a year, he was removed from a case by the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the second time–an extraordinarily rare outcome for a federal judge. And in 2014, a law professor said Schwab performed “judicial gymnastics” to issue a legal opinion declaring President Obama’s immigration actions unconstitutional.

Bartels expressed contrition during his sentencing on January 27, 2021. “I made a stupid mistake, and a lot of people have had to pay for it,” he told the court. “I think back to May, leading up to what happened, I was hopeless, angry, frustrated. I had all these emotions and I went out and I made a problem worse.”

Schwab considered Bartels’ mental health, lack of criminal history, his acceptance into a university, and his father’s testimony when determining his sentence. In part, Schwab told the court, he arrived at his judgment of a day in custody with the United States Marshals Service, followed by six months in a halfway house, “in light of the need to have the defendant become a productive citizen as quickly as possible.” Bartels was also ordered to pay $1,000 in restitution.

Nine months later, Bartels’ sentence was brought up in the defense of both Da’Jon Lengyel and Christopher West, the Black men who threw paper on the police SUV fire. Their lawyers argued their cases at sentencing on the same October day–Lengyel in the morning, West in the afternoon–in front of Judge J. Nicholas Ranjan, a 2019 Trump appointee.

George Allen

To be removed from my children and family feels like a Social Death, I am alive but the people I know are now only voices that come through phone lines in increments of 15 minutes, 500 minutes a month, seeing their existence only in photos and letters and vice versa.

They were fighting an uphill battle. Both of their clients had criminal records, and they waived their clients’ rights to seek a variance below the sentencing guidelines as a part of their agreement with the prosecution. “That’s the first time I’ve had to do that in almost 30 years of practicing law,” Lengyel’s lawyer, Martin Dietz, told Ranjan. But he took some solace, knowing that he could not waive Ranjan’s discretion to choose less prison time. “Now, I would ask you to consider the fact that Brian Bartels’ sentence is extremely, extremely light for the person that incited that event when you fashion an appropriate sentence.”

West’s lawyer, Frank Walker, made a similar plea later that afternoon. “And the main factor that jumps out to me is the need to avoid any sentencing disparities,” Walker told the court. He couldn’t say how much Bartels was to blame for everything that happened, but based on the judgment he received “versus what Mr. West and Mr. Lengyel is facing, the question remains the same. What makes sense?”

Judge Ranjan applied a similar analysis to the two defendants: Both men had opportunities to disengage from the situation, but did not. Bartels had no criminal history, these men did. And he was bothered that the SUV inferno detracted from the memory of the previously peaceful protest. “You just see the pictures of the police car on fire,” he said during West’s sentencing. “I think in a certain sense it takes away from the First Amendment rights and a message, I think, that was meant to be conveyed by many of the people there.”

Lengyel and West received 27 and 48 months, respectively, three months below their guideline minimums. The restitution they were each ordered to pay was 25 times that of Bartels–$25,000.

Within a week, Raekwon Dac Blankenship, who had spent roughly 16 months in jail, was sentenced to six months in a halfway house by Schwab for jabbing his makeshift sign at a police horse. He had already been sentenced to two and a half to five years for his actions during the protest in state court, so it would be some time before he would submit himself to the reentry center.

This may seem like an instance of double jeopardy, but the Supreme Court has long held that a person can effectively be prosecuted twice for the same crime as long as the charges come from different governments. In this case, the charges are from federal and state governments.

Similarly, George Allen faced parallel state and federal charges for throwing a piece of concrete at an occupied police car that went through the passenger window and bruised an officer’s arm. The bruise was minor, and Allen’s federal lawyer, Patrick Nightingale, told the sentencing judge–Schwab again–that the state court had agreed to probation with no incarceration. In light of the details surrounding the case, Nightingale told me he was confident his client would, at worst, be sentenced to the low end of his guideline range, eight months.

On December 1, 2021, after Judge Schwab announced Allen’s federal sentence, he recounted that Allen had a full-time job, supported his three children, and had primary custody of the eldest. Despite this knowledge, Schwab sentenced the Black man to a year and a day in prison, along with about $600 in restitution. Schwab’s primary reason for the harsher sentence was that Allen launched his projectile at an occupied vehicle.

Allen’s head was racing. “Wow, this very old white man has the complete power to determine and alter the trajectory of my life,” he wrote me through his prison’s email system. “I couldn’t believe that I was about to spend a year and a day inside the walls of a Human Warehouse.”

He was sent to Federal Correctional Institution, Hazelton, a prison in West Virginia near the Pennsylvania border nicknamed Misery Mountain. Allen was on multiple medications and suffered severe anxiety leading up to the moment he would turn himself in. Once he was inside, he wrote that he was denied his medication. He also told me that he attempted to take his life by cutting his wrist soon after being incarcerated.

“To be removed from my children and family feels like a Social Death,” he wrote. “I am alive but the people I know are now only voices that come through phone lines in increments of 15 minutes, 500 minutes a month, seeing their existence only in photos and letters and vice versa.”

His lawyer was aware of the suicide attempt and reached out to the prison to see if Allen was being given his medication, but said he received no response. When I inquired about the attempt, the prison’s executive assistant emailed a statement that read, “For privacy, safety, and security reasons, the Bureau of Prisons (BOP) does not comment on any individual inmate’s conditions of confinement, including medical and mental health information.” Generally speaking, the assistant wrote, the prison screens inmates for suicidal ideation and has multiple measures in place to prevent suicide once people are incarcerated.

The least that a city owes its citizens is to get this right, to protect them and to give them the kind of service that everybody expects.

David Harris, professor and expert on law enforcement and race at the University of Pittsburgh School of Law

At the start of 2022, Schwab sentenced Joseph Craft, the white man who twice hit a police vehicle with his skateboard as it drove past, vandalized another vehicle that would later be set on fire, pulled a large sidewalk planter into the street to the obstruct police, and threw pepper canisters back at officers during the riot. His previous criminal history was greater than Allen’s. Using the guidelines, the prosecution requested 4-10 months of incarceration.

Bartels’ sentence was invoked once again by the defense since the court should seek to limit the appearance of sentencing disparities. For this case, Schwab departed from the guidelines and issued another sentence of a day with US Marshals, followed by a year of house arrest.

“This was a criminal act. The defendant shows very little, if any, repentance for what he did,” Schwab told the court. “I did not do a sentence of incarceration simply because he is working full time, and I think it’s a more effective sentence to have him … remain a productive worker.”

After six months, Craft’s lawyer filed a motion to have the home detention lifted because it was cutting into his work availability. The US Attorney’s Office challenged the change; Craft had already been given a lenient sentence, they argued. Schwab lifted the house arrest and put him on a curfew.

The implications beyond Pittsburgh

At least three other white men were sentenced between Bartels and Craft. Matthew Michanowicz, a 52-year-old, planted homemade explosives near the PNC Plaza downtown the day after the riot. Possibly due to concerns for his mental health, after 18 months of incarceration, he was sentenced to probation by Judge Donetta Ambrose, a Clinton appointee. Andrew Augustyniak-Duncan threw concrete at police officers and was sentenced to the minimum of a guideline range—16 months below what the prosecution initially argued for. And Nicholas Lucia received 24 months after agreeing to a plea deal for throwing his small explosive at police. Jordan Coyne was sentenced to 18 months in early January following a plea deal.

The clerk of court for the US Western District of Pennsylvania, Brandy Lonchena, sent a written statement in response to BlackPittsburgh’s findings on the differential sentences that stated the court adhered to the standards of federal sentencing. And the defendants did not challenge the judgments post-sentencing. She wrote that “in any group of cases, there are often material differences in the offense conduct and criminal conviction history of the defendants, leading to different results from the individualized calculation of the Sentencing Guidelines.”

Tanisha Long, founder of Black Lives Matter Pittsburgh, told me that she had many problems with “well-meaning white people” who wanted to turn up the temperature during protests. “Let’s turn it down,” she told them. “You’re not gonna get charged the same way we are.” She’d have to run interference with the Black people as well so they wouldn’t get swept up in the energy. “They are not gonna sacrifice their bodies for you,” she’d say. “The police won’t let them, and that’s the truth of it.”

George Allen was released from prison on December 28, 2022, and was mandated to stay in a halfway house for the month remaining on his sentence. He thought his life was over during the depression leading up to his incarceration. Now, he’s hoping to rebuild. “I’m trying to get my life back in the amount that I can, seeing that I’m now a felon,” he said.

There have been at least 369 people who have been charged with federal crimes connected to the George Floyd protests in the United States, according to data collected by the Prosecution Project, a research platform dedicated to tracking criminal cases involving political violence. The data is incomplete, but Pittsburgh’s 12 cases that I found place it among the top five totals for a city.

Portland leads the way with 96 people charged federally. While Trump’s Department of Homeland Security burned through taxpayers’ money to chase an antifa boogeyman, some Black people in the west coast city had an issue with white agitators hijacking the protests, according to research being done by sociology professor Shirley A. Jackson at Portland State University. Her interviews with more than 50 Black people in the Portland area found that many believe the disruptive actions harmed the goals of social justice.

“I find it problematic when I see a group that is participating due to its own privilege–as being primarily white,” she told me, “when they are purposefully being obtuse when it comes to the backlash that their behavior, their actions, can have on a movement such as Black Lives Matter.”

When former Attorney General William Barr announced on May 30, 2020, that he wanted to “have law and order on our streets” following the murder of Floyd and that he was going to use the tools of the Department of Justice to “take all action necessary to enforce federal law,” he was utilizing a playbook as old as the fight for civil rights. The federal criminalization of civil disorder, the Civil Obedience Act of 1968, was codified in the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which emerged from the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., and the nationwide riots that ensued.

Gloria J. Browne-Marshall, a former visiting professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and author of Race, Law, and American Society: 1607 to Present, said she was concerned about the weaponizing of the courts to undermine protests and how the severity of punishment may be breaking across racial lines.

“The rule of law says that everyone has equal protection, should be sentenced and treated fairly, and similarly in court. However, the role of law has been for hundreds of years one filled with racial disparity and rife with discrimination,” she said. “To have such differences in the actions of the defendants and yet have those who had acted with more violence, be treated more leniently, shows that this is more the role of law than the rule of law.”

Sean Campbell is an investigative journalist based out of New York City. His recent work has focused on social justice and modern civil rights.