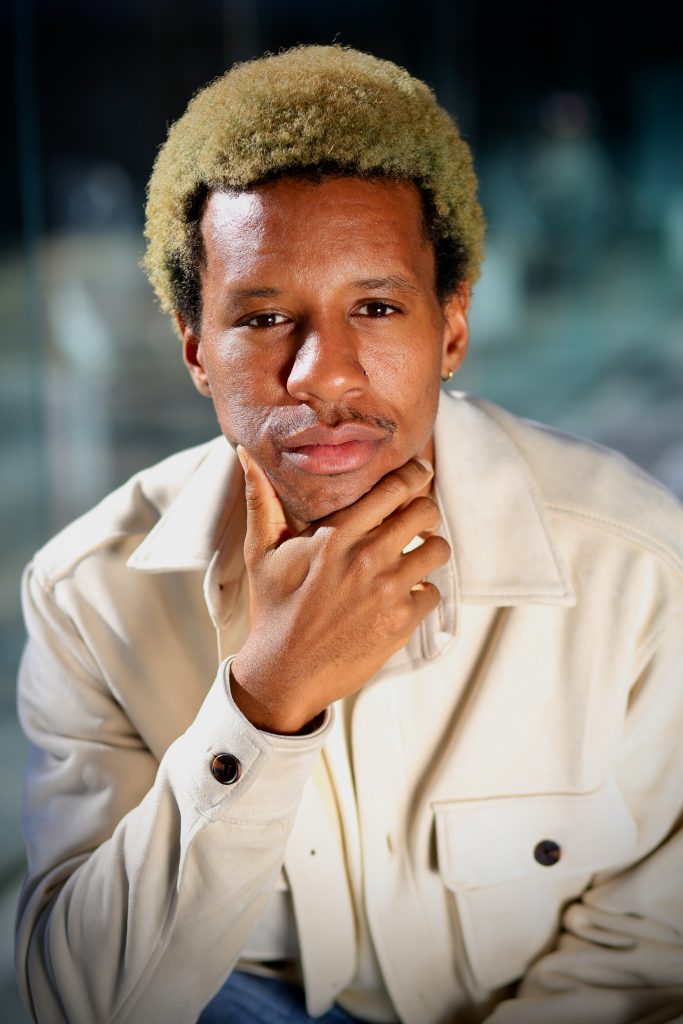

Inside his Carnegie International participatory exhibit, ‘The Proposal.’

By BlackPittsburgh.com STAFF

Earlier this spring, multidisciplinary artist Malcolm Peacock returned to Pittsburgh to again participate in the 58th Carnegie International—”Is it Morning For You Yet?”

Peacock, whose work was featured alongside over 100 artists and collectives from around the world, curated “The Proposal”— an interactive Black art performance experience steeped in an aura of mystery – not unlike its creator.

The interactive presentation, which featured a diverse group of Black Pittsburghers whose identity was not revealed beforehand, was made to be viewed one person at a time. “The Proposal” ran on four select days throughout the six-month-long (September 2022 – April 2023) Carnegie Museum of Art’s international contemporary art show—the second largest in the world.

It’s a proposition for what I want to envision as the present and/or future of public space.

Malcolm Peacock

Peacock, 29, was only in Pittsburgh for a short time, but the imprint of “The Proposal,” which centers on how Black people can exist as our whole selves in public spaces designed and designated for the traditional (read: white) fine arts world, will likely resonate with our community forever.

“I’m a stickler for minimalism,” Peacock says, reflecting on his creative process in a recent interview with BlackPittsburgh.com. He describes his artistic practice as “bare bones” and “low maintenance.” But this version of minimalism is less about the aesthetic category and more about Peacock’s views on labor.

“One of my mottos for life is: how can I get through the shit-storm of living in this landscape, giving as little of my time away to the man as possible. And you can totally look at the museum as ‘the man,'” he says.

Now based in New Orleans, Peacock grew up in Baltimore. He developed his affinity for the arts early on from his mother and his grandfather, whose rationale about work still shapes Peacock’s practice.

“My grandfather was always trying to find the way he could take back as much of his time as possible,” he says. “Even if he didn’t know what to do with that time, he knew that time was his greatest resource.”

Time, for Peacock, is indeed a resource – a pool from which he creates and generates opportunities for himself and for others. He says it shows up as much in “The Proposal” as in one of his most successful shows – “We Served … and they felt tiny bursts along the horizon,” launched in New Orleans (in 2022).

No one should misinterpret Malcolm’s minimalism as a diminished commitment to craft. For him, understanding how labor operates in today’s capitalist economy is essential to his artistic vision.

“I am ‘anti’ a lot of different labor systems,” he says. “It comes up prominently in my art and throughout my work.”

I was uninterested in this idea of these people as performers. The piece was supposed to be about Black autonomy and these autonomous acts without surveillance.

Malcolm Peacock

Peacock visited Pittsburgh for the first time in February of 2022 in preparation for his contribution to the Carnegie International series. He says he was struck by the conservatism of the museum. As he waited for a meeting with the program’s curators, Peacock began to ruminate on an idea: “the nature [or] essence of a Black autonomous space.”

“The piece is a test in a way,” he says. He explains that for museum installations, the medium of any work is generally provided in the brief description that accompanies it, whether it be a painting, mixed media, photography, etc. The solitary word “Proposal” was the description for the medium of his installation at the Carnegie Museum of Art.

“It’s a proposition for what I want to envision as the present and/or future of public space,” he says. The artwork is an interactive space wherein four Black women from Pittsburgh are paid for their time to create, interact, and converse. But the experience is more complex than can be described in words.

“You arrive at the museum,” Peacock says. “You sign up, and you may never be admitted. Most people are never admitted. Only so many people can be admitted because there are different time constraints and experiential parameters.”

“The piece is really not for the public. The actual experience is for the women in the room. They (the Black women) are invested in whatever they are doing, and a lot of times I’m not there. I provide them with things that they want – art supplies, instruments . . . I get their lunch.”

“I take the running as a meditative and spiritual process that can be both physically and mentally taxing.

Malcolm Peacock

If this all sounds too mysterious to you that’s OK with Peacock. The mystique is a feature of the art. Peacock is wrestling with a fundamental question: Is it possible for Black people, and these Black women from Pittsburgh in particular, to choose how they would occupy their time?

“The point of the project was that they did what they wanted under terms of no surveillance,” Peacock explains. “They cannot light shit on fire, but other than that, they just do what they want.”

He continues: “It’s really a living organism. I was uninterested in this idea of these people as performers. The piece was supposed to be about Black autonomy and these autonomous acts without surveillance.”

Part of the idea for the project grew out of how Peacock felt policed inside of the Carnegie Museum of Art when he first visited back in 2022. He came out of the experience and spent months planning what an autonomous series of actions could be in a designated artistic space. What does an autonomous Black life in public feel like?, he asked himself—and all of us.

The presentation also evolved from Peacock’s passion for long-distance running. He says he is good enough to compete professionally, but art remains his primary career. When we spoke with him, he shared that he ran several marathons over the last few years and sees some relationship between his art and his competitive running.

“Absolutely, they go hand in hand,” he says. “I take the running as a meditative and spiritual process that can be both physically and mentally taxing.” For Peacock, running doubles as a practice through which he copes with past challenges in life, including a traumatic experience which he does not reveal in detail.

“There are larger forces and thoughts that I tap into and there is a momentum,” he expounds. “A push that I get from considering the lives of others that are not my own when I’m out on the road.”

Instead he directs us to an audio recording on the subject. It’s a 30-minute treatise on Peacock’s practice for art, for life, and for survival. He delivers it as he is running. It is a revelation about him and his philosophy for both creating and surviving.

It’s a clue, or a cue, for people to better understand the artistic life of Malcolm Peacock.