Noted social justice scholar discusses the Black working class, race, and reparations

By Ashanti McLaurin and Ervin Dyer

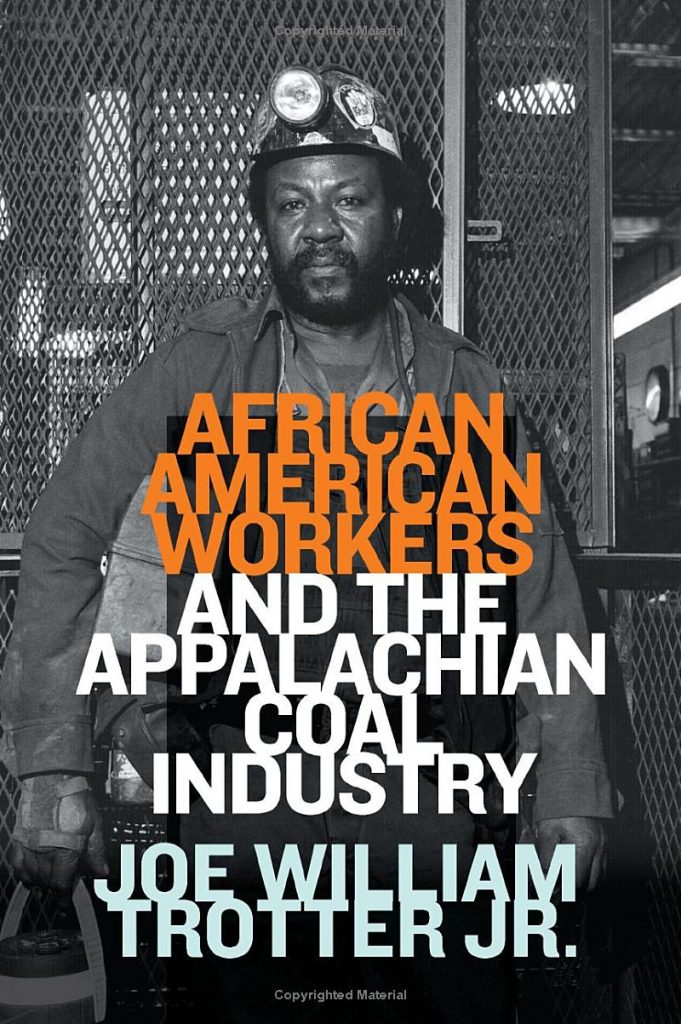

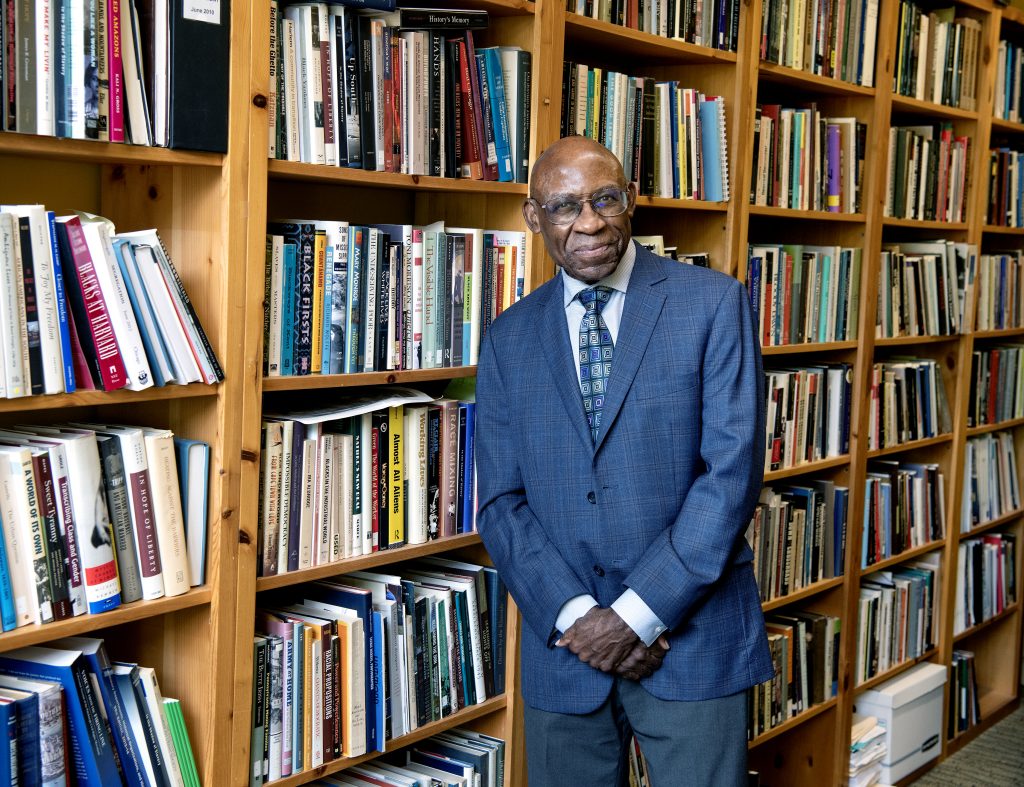

Dr. Joe William Trotter, Jr. is the Giant Eagle University Professor of History and Social Justice at Carnegie Mellon University. For nearly a half-century now, he’s studied issues of race and class, particularly examining how they affect the Black working class. A respected and thought-provoking scholar and author, Trotter’s story begins in a deeply segregated South where he was born in 1945. His experiences and studies have taught him that the Black working class has made enormous contributions to family, community, and America beyond just labor power. His 2022 book African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry continues his research on Black labor, as he elaborates on the “intellect of coal mining.”

Trotter, himself the son of a coal miner, believes that one’s beginnings shape one’s destiny. He received his B.A. degree from Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin, and his M.A. and Ph.D. degrees from the University of Minnesota in 1980. Before coming to Pittsburgh, he taught at the University of California at Davis for five years.

At Carnegie Mellon, Trotter is the founder and director of the Center for African American Urban Studies and the Economy (CAUSE), which researches Black labor and the Black working class. Trotter is also spearheading a broad group of scholars and community members to develop a report on reparations, advancing the conversation and devising action steps on repairing historical and contemporary inequalities in the city and the Western Pennsylvania region.

You have to factor in the way that race works to undermine the Black working class so that Black workers and wage earners are not treated on an equal plane as their white counterparts.

Joe Trotter, Jr.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Tell us your background and how you grew up.

I was born in southern West Virginia, an environment that was very segregated. I was educated in Jim Crow schools. All of my teachers were Black, and all of the students were Black.

My mother and father were migrants from Alabama. They moved to southern West Virginia, where my father became a coal loader. My family [consisting of 14 children] was one of the largest in the town.

What else do you recall?

Working families and low-income families didn’t have paved streets, for example, in front of our houses. There were dirt roads. That was common to all. But I saw social distinctions and material distinctions show up in other ways. For example, there was one family that had carpentry skills. And the father and his sons (he had about four sons) were able to get lumber and build a new addition to their house, [expanding] the room that they could live in. They became the elite family among the working people because they could have an additional room, which signified material gain. Then the other thing is that when I was growing up, there was no indoor plumbing. We had to go to an outhouse for the bathroom. Later, many in the community did get electric stoves and that type of thing, but I grew up essentially in a place where we had to make fire in a wood-burning, coal-burning stove. My mother had to cook on a coal-burning stove for many years before we got an electric stove.

Growing up the son of a coal miner, what did you notice about class differences?

Because we lived in a coal company town, all of the homes were owned by the coal companies. Many times, the families in our community did not get cash for their work. They got a script book that they had to use at the company store. This happened to all the families who were part of this coal-mining community.

So, in a sense, there was not much class difference among the Black families because everyone was considered lower income. They were pretty much “equal” in that everyone in the community was at the same place economically.

I remember that among the Black people in my area, there tended to be relatively minor differences between working people or poor people. Most of us were essentially children of coal miners. Our mothers, for the most part, did not work outside the home. They worked gardens and canned food, cared for the children, and did household management. Though there were a few who did, most of them didn’t go to somebody else’s house to work as domestic servants.

How have those experiences shaped you and your research and academic interests?

This environment of coal mining shaped my attitude toward labor. I became very interested in the way people who come from working-class families could achieve. They face great odds, but at the same time, we learn that, over time, people coming out of these families could often achieve amazing things, overcoming incredible obstacles. It may be starting to change, but, too often, I think scholars and society at large have downplayed the role that coal miners and working-class people played in the economy, culture, and politics. Far too often, we’ve only wanted to talk about the role played by people who had more education and participated in the professions – the teachers, the doctors, the lawyers, and so on.

What is your definition of the Black working class?

My fundamental definition is pretty classical; it’s what they would call a Marxist definition. It argues that the working class is a group of people who work for wages and do not own lots of wealth or don’t have a great deal of formal education. As a consequence, they’re dependent on the wages that they get by selling their labor power in a marketplace that tries to squeeze wages down to the lowest point that the market will bear. Working people are the most vulnerable part of a system of capitalist development.

That’s a class definition. But then you have to factor in the way that race works to really stratify and undermine the so-called Black working class so that Black workers and wage earners are not treated on an equal plane as their white counterparts. If you do that, you will see Black workers have historically, and even contemporarily, had access to fewer supervisory jobs and they have to take jobs that require them to follow orders a lot more than their white counterparts.

Black working class people are energetic, creative people. They are thinking all the time about the system that they are living in and they understand that system in ways that we don’t often give them credit for. They understand how the top benefits from their labor.

Joe Trotter, Jr.

What made you want to create the Center for African American Urban Studies and the Economy (CAUSE)?

The reason for CAUSE is that I developed my career studying Black people in cities. In fact, the urban Black experience was the first foundational study that I conducted as a professor. That study was called “Black Milwaukee,” and it was a study of African Americans in that city between the two World Wars and the Great Depression. As I started to research more and more on African Americans and the urban experience, I realized that Black urban historians were writing histories of African Americans in all kinds of cities – Chicago, New York, Detroit. Even Southern cities were beginning to come into play. We decided to create CAUSE as an institutional instrument to help bridge historical studies on the Black urban experience with the more contemporary sociological, political science, and other kinds of research on the current moments in urban African American history.

What else is CAUSE innovating?

When we opened [CAUSE] back in 1995, we wanted to do two things. First, we wanted to be an effective instrument for bridging historical and contemporary scholarship, bringing multiple disciplines together. Second, we wanted to find a way to make this information available to the larger community. We said that we wanted this program to welcome African Americans from the community to share their voices, to participate as partners in the research and the solutions that come from it. We wanted to find a way of involving scholars in a discussion with the community in order to craft the next generation of scholarship that would not only be influenced by academic researchers and their disciplines, but also be influenced by the interplay between scholars and the ideals that are developing within our surrounding communities.

What is the next step for CAUSE?

The creation of opportunities for the next generation has to be one of our top priorities. We want to bring more young people into the field, making sure more young people get undergraduate training that will prepare them for graduate studies. We have established a unique Postdoctoral Fellowship Program. Whereas many postdoctoral fellowship programs ask the fellows to teach and to do their research, our fellowship excuses them from teaching. We want them to concentrate on writing and doing any additional archival research that is needed because we want to see their books published, on the shelf, and in the hands of scholars and the community.

The families in our community did not get cash for their work. They got a script book that they had to use at the company store. This happened to all the families who were part of this coalmining community.

Joe Trotter, Jr.

Tell me about CAUSE and the reparations project?

We are completing a three-year A.W. Mellon-funded reparations project. This project pulls from across disciplines. We’re engaging oral histories from local citizens, engaging sociologists, nonprofit social service leaders, other historians, and narrative writers. We’re going to present a set of recommendations for the city of Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania at the end of this year. We anticipate that, moving forward, the recommendations will be the foundation for a broader and more intense engagement on the issue of racial and class inequality, and so we are hoping to find a way to institutionalize the fight for reparations.

What evidence is present in Pittsburgh that shows us what historical and contemporary systemic inequality looks like and why it needs to be repaired?

The way we need to understand it historically and as historians is that systems of inequality and oppression have not remained exactly the same over time. What we have to recognize is that there are moments where inequality takes a particular form. In Pittsburgh, the reason we believe we need a new history of African Americans is because so much of the narrative on African Americans in Pittsburgh begins with the rise of the steel industry, [and] the way in which the industrial period was the centerpiece in so much of African American life. But what we’re trying to say is that there was a backstory, a time before industrialization, and that story included slavery in Western Pennsylvania. The first generation of African Americans in the city were enslaved people who were owned by other people in the city. It is important to consider this as a root factor in how inequality began to impact generations of African American life across income, health, education, and more.

What do you want college students to learn about the Black working class?

I want people to take away from my courses on the Black working class that these people are energetic, creative people. They are thinking all the time about the system that they are living in and they understand that system in ways that we don’t often give them credit for. They understand how the top benefits from their labor. Also, I would like for students to gain a respect for the intellect and capacity of the working class in forging an agenda in trying to solve their own problems. I would like students to understand that the working class are not just victims, which you hear so much about, but that they are also people at the bottom who possess dynamic energy and are able to channel that energy into activist programs and projects.

I have found that they are constantly trying to develop strategies that will help them get out of the condition that they are in. Some of those strategies are very individualistic. They do things as individuals that they feel they must do, but other strategies are very collective. When you see them join churches of all kinds, they’re making a statement about who they are as a people and their capacity to congregate and come together and to begin forging some kind of bonds with each other. Those bonds helped them to make decisions about how to struggle and survive.

Ervin Dyer is a writer who focuses his storytelling on Africana life and culture.

Ashanti McLaurin is a writer interested in social justice and Black culture.