New director of Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures uses his Haitian roots to foster storytelling as community building.

By Ervin Dyer

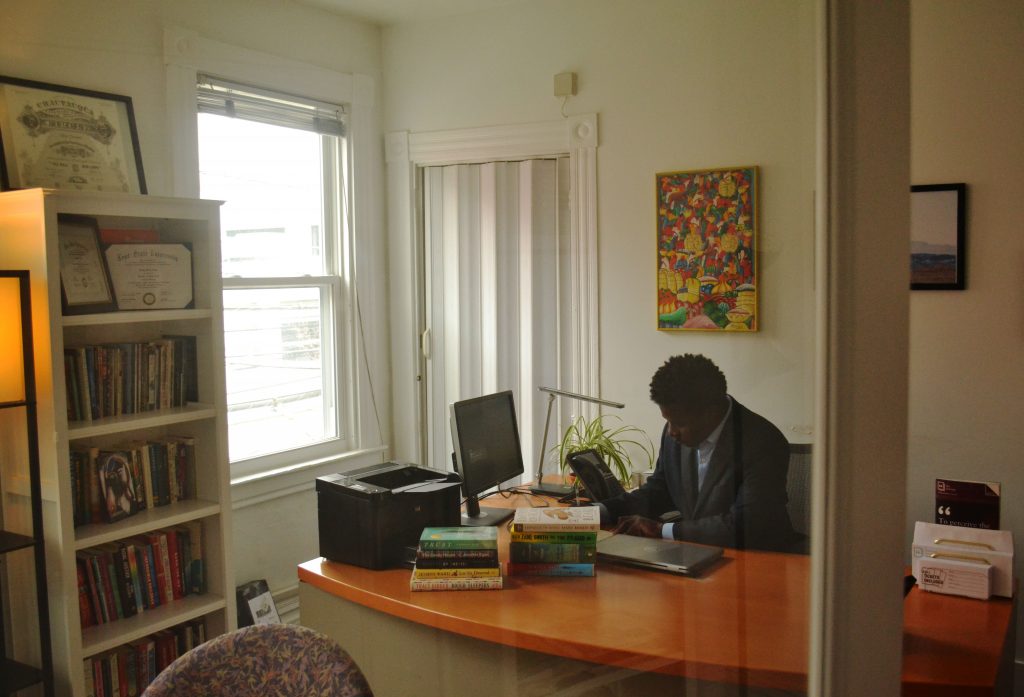

In September, Sony Ton-Aime was named the executive director of the Pittsburgh Arts & Lecture Series. Formerly the Director of Literary Arts at New York’s Chautauqua Institution, his work in arts and literature began a world away from western Pennsylvania.

Ton-Aime, 33, was born and raised in far northeast Haiti in Ouanaminthe, a town near the border of the Dominican Republic. His father worked primarily as a security guard and his mother was a marchand, a market woman who purchased bundles of second-hand clothing and resold them. He says they were “hard workers who could make butter out of water.”

Ton-Aime was deeply influenced by storytelling in his community. In the night, especially during harvest, as his father and other neighbors gathered to shuck corn, they would joyfully tell stories. It is an oral tradition that embodies what the Haitians refer to as krik krak, a call-and-response rooted in African culture.

As he turned older, Ton-Aime, the middle son of five siblings, went to Institution Univers, a private high school, where he nurtured his love of reading and became editor of his school magazine. The 30-minute walk to the school and the lessons learned there, he says, took him out of his “bubble” in Ouanaminthe, exposing him to differences in class, religion, and world views of the human condition. Being exposed to different people and cultures, Ton-Aime says, fueled his work as a writer and arts administrator.

“I’ve been trying to live a life where I connect people so they can tell stories, so they can find common ground,” he says. “To know that there are people who are living worse lives or better lives and to know that everyone is human and can live with dignity, with love.”

In 2010, Ton-Aime earned a scholarship to Ohio’s Kent State University when he was 19, and then returned to Haiti, working there for two years. His love of poetry and storytelling brought him back to Kent State. There, he earned a Master of Fine Arts degree in poetry and did a fellowship with the university’s Wick Poetry Center, where he created platforms to share stories from the margins and from the mainstream.

After a brief stint as a program coordinator at Lake Erie Ink, a Cleveland nonprofit focused on youth and creative writing, he went to Chautauqua Institution. He was on stage there in August 2022 when a knife-wielding man rushed Salman Rushdie, severely injuring the writer.

In this Q&A with BlackPittsburgh, condensed for clarity and length, Ton-Aime talks about Haiti’s influence on his work and his goals for the Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures Series.

What was it like growing up in Haiti?

This is a question that makes me so emotional, but it also allows me to share my testimony of the communal life in Haiti. We didn’t have much when I was growing up. But when I was in elementary school, I was getting good grades, and my parents and older siblings made the decision that the family would sacrifice everything for me to attend a private school. They never told me. An uncle told me in 2015, five years after I came to the States. It was easily one of the 10 best schools in Haiti. And that’s how I ended up attending Kent State [and] getting an undergraduate degree in accounting.

Why accounting?

I studied accounting, because I could not speak English well enough [his first languages are French and Haitian Creole]. I had heard numbers are the same everywhere, so I studied accounting. But then, I decided to come back to my first love, which was writing. It was a big risk, because you can major in poetry, but I had heard “poetry is poverty if you just add a V.” So, it was very difficult. But telling stories was something I loved, and my mom would always tell me “If you really love something, you will be able to make a life out of it.”

Tell us about story time in Ouanaminthe, Haiti.

It’s time for family. It’s time for community. In Haiti, it’s rare that everyone will be together by dinner hour. That comes later in the night, and that becomes story time. As a young person, I would consume those stories because they were fun. But it’s also how I learned about my grandparents, how I learned about my parents’ childhood. And so, I always attach the idea of telling stories (of reading stories) as happy times. The times you can be fully yourself. So, that’s why stories are so powerful in my life and so important to me.

What of the Haitian experience comes with you to Pittsburgh?

Haitians have so much to share with the world. That’s why it’s so important that I’m here right now because I have something very important to share with the world through my readings. But also, through the voices I will bring to Pittsburgh.

I’ve been trying to live a life where I connect people so they can tell stories, so they can find common ground to know that everyone is human and can live with dignity, with love.

Sony Ton-Aime, Executive Director of Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures

What are you working on now?

I’m working on a collection of poetry about the Haitian Revolution. I believe that studying the Haitian Revolution can get us through whatever we fear about the future. Imagine people who were enslaved for 200 years and who were taught that this is where they belong. And then for them to one day say: “No, there is something else. We are going to create a future that no one in our condition has ever seen before.”

And so, every time people feel overwhelmed about the future, I say, “Put yourself in the position of the enslaved people in Haiti.” They were told the same thing. Yet, they imagined something different, and they made it happen.

Even after emancipation, with Jim Crow, there were people who put their lives in danger to create this future that we’re living right now. People imagined it and created it, and then told stories together. And that’s why stories are so powerful. They told stories about the future, and then we’re living it right now. That’s why we need to tell better stories to our children, to our grandchildren. Stories about the future, stories that are hopeful, stories that are daring.

You bring storytelling into a spiritual dimension – in that stories offer the hope of things unseen. How do stories build community?

One of the most important things for change is telling stories. It is the thing that brings us together. We can agree on characters, we can disagree, but the discussion brings everyone to the same place. Second, storytelling creates a blueprint that tells us we can imagine something we’ve never seen before, and we can work toward that. Third, stories make things personal, because we all live in stories. So, every time we hear a story, we become the main character, because we see ourselves in the people.

After emancipation, there were people who put their lives in danger to create this future. People imagined it and created it, and then told stories together about the future, and then we’re living it right now.

Sony Ton-Aime, Executive Director of Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures

Much of your early experience was with oral tradition, but who are some of your favorite writers?

I love the Haitian writer Justin Lhérisson. He was writing in French, but he would write like the people that I grew up with and not cheapen how they spoke. Other Haitian writers I like, who are writing very much of the Haitian experience, are Jacques-Stéphane Alexis and Frédéric Marcelin, who wrote during the U.S. Occupation of Haiti, criticizing the Americans but also the Haitian bourgeoisie who sided with the Americans.

When I came to the United States, I read the masters: James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston. Today? I read [Haitian native] Edwidge Danticat and I tend to gravitate around writers who are writing about things in the margin.

What are you bringing with you from Chautauqua Institution?

One thing that I learned from Chautauqua, especially during the [Rushdie] attack, is the power of intentional leadership. When we are among writers, we feel as one. To see the way that 70-year-old, 80-year-old people rushed to the stage to protect someone they connected with (someone they did not know personally, but whose writing they connected with) was the most important thing that I could have learned from this horrible day. It told me that when it comes to community, we need leaders who are intentional about bringing people together. When that happens, we can move mountains. So, I’m bringing that to Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures.

Final thoughts?

First, I want to make sure that the community realizes that [Pittsburgh Arts & Lectures] is a community, and we can rely on each other. And then I want to broaden our bubble, to broaden our community so different voices can be heard. I’m a Black man living in America, and my experience is very much an experience of an outsider coming to America. But for me to say, “Oh yeah, I’m a Black man, I can bring the writers that I think will be a great fit for Pittsburgh or the Black community in Pittsburgh,” would be totally wrong. I need to hear from the community and from different partnerships about what they want to hear.

Ervin Dyer is a writer who focuses his storytelling on Africana life and culture.