For more than a decade in East Liberty, the Selma Burke Art Center taught thousands of children the art of sculpting—and made its mark during the Black Arts Movement’s heyday.

By Tracy Sharpley-Whiting

Pittsburgh’s storied history as a center of Black creative culture has been well documented—from pioneering African American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, jazz composer and pianist Billy Strayhorn to Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright August Wilson. Lesser known today is sculptor Selma Burke, whose Selma Burke Art Center, among other cultural institutions, helped solidify Smoketown’s place in the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and 1970s.

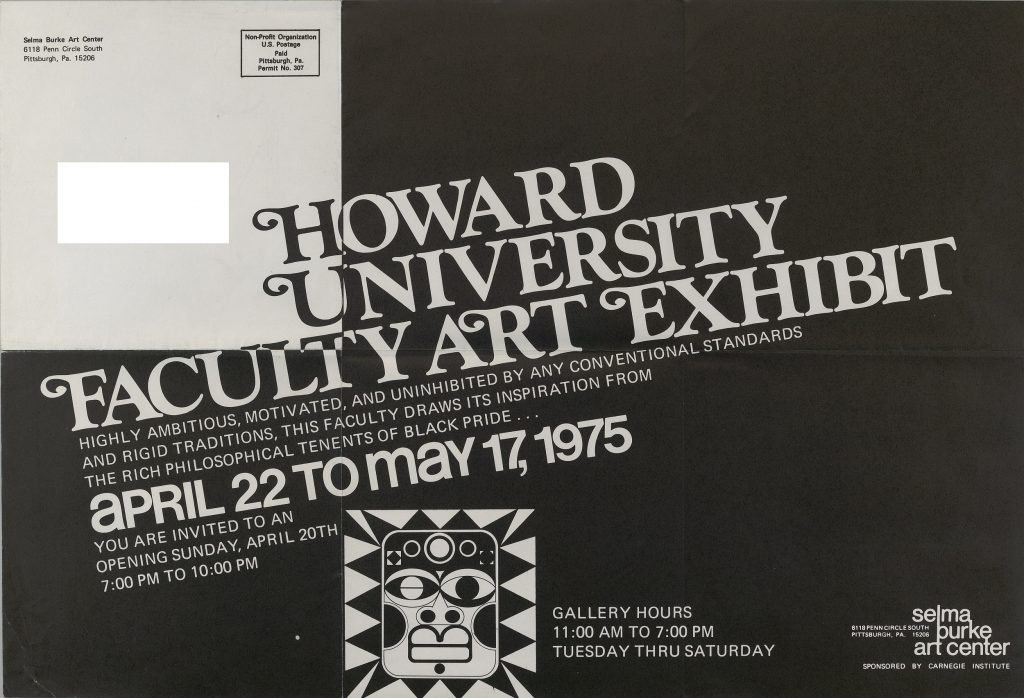

Promotion for Selma Burke Art Center events: poster for a 1980 Puppet Show and postcard for a 1973 mixed media exhibit by the Black arts collective Mbari—courtesy of A.W. Mellon Educational and Charitable Trust Records, 1930-1980, AIS.1980.29, Archives & Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

Located in East Liberty from 1971 to 1982, the Selma Burke Art Center offered classes in a range of visual and performing arts—from drawing and painting to dance and sculpture. Funded by Carnegie and Mellon philanthropic trusts, the center’s namesake, Selma Hortense Burke, was one of America’s leading sculptors (who should be famously known for her bas-relief of Franklin Roosevelt’s profile on the U. S. dime piece).

The center occupied a former Mellon Bank Building at 6118 Penn Circle South. And Burke took her teachings on the road to drum up students for the center, offering sculpture demonstrations in Pittsburgh’s public schools. Over the course of five years, she educated more than 60,000 children on the art of sculpting. The center also played host to the Howard University Faculty Show in 1975 that featured works by transnational diasporic visual artist Jeffrey Richardson Donaldson and the AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists) collective, which was founded in 1968 in Chicago, and played an integral part of the Black Arts Movement.

Born December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina, Burke was educated at Washington D.C.’s black funded and operated Nannie Helen Burroughs School for Women and Girls, where, according to Burke, girls were encouraged to become ladies by wearing “silk-ribbed stockings, patent leather Mary Janes and gloves.”

“I wanted to be a lady but also an artist,” Burke later recalled. “One day, I was mixing the clay and I saw the imprint of my hands. I found that I could make something . . . something that I alone had created.”

The clay soil and wood in North Carolina provided the building blocks of the three-dimensional form she would eventually master.

Despite these early artistic aspirations, she was encouraged by her family to pursue a more practical career, and so she studied nursing. She arrived in New York in 1928 as a private nurse, at the tail end of the Harlem Renaissance, and a year before the collapse of the American stock market and the onset of the Great Depression.

Art is the basis for everything.

Selma Burke

Burke soon took up with the avant-garde New York crowd that included Harlem Renaissance writer Claude McKay. Burke maintained the two eventually married (wed twice and divorced twice), though historians have yet to confirm a New York marriage license. Bohemian though she may have been in the artistic sense, she was clearly attuned to issues of propriety in an era where living together unmarried was not yet fashionable.

Burke pursued coursework in sculpture at Columbia University in 1936 and 1937 and worked as a teacher of sculpture with the Harlem Community Art Center (HCAC). With the support of a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and a Hans Bohler Award for study in France and Austria, she left New York and McKay behind to pursue art in Paris and Vienna in 1938 and 1939.

Europe was chock full of possibility and promise. Paris was an artist’s haven. The City of Light conferred status that was often withheld in the United States from Black women artists. Only financial resources (rather than race and gender) limited freedoms. It was not so much that the French were colorblind; they were simply not color averse. Burke’s status as an American also greased the wheels of social acceptance.

I wanted to be a lady but also an artist.

Selma Burke

In Paris, Burke sought out the neoclassical sculptor Aristide Maillol whose work focused on large-scale classical female nudes cast in bronze. Such was the freedom of Paris; there she could fully explore her interests in African art.

“I have known African art all of my life,” she said, reflecting on that period in her life. “At a time when this sculpture was misunderstood and laughed at, my family had the attitude that these were beautiful objects.”

The city had played host to the Colonial Exposition seven years earlier in 1931. With its displays of pillaged and pilfered African art and peoples in human zoos, the Exposition brought Africa to Paris. It never left, influencing the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

In 1941, Burke returned to New York City and Columbia University where she completed a Master’s in Fine Arts. That same year, she won a national competition for a commission to sculpt the late President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Burke had two sittings with the president during which she sketched him for the bronze plaque that hangs today in the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C. Though John Sinnock, the engraver whose initials appear on the Roosevelt dime, would vehemently deny his obverse was influenced by Burke’s plaque, scholars argue that the striking similarities undercut Sinnock’s objections.

Next, Burke set up her first eponymously named art school, the Selma Burke School of Sculpture at 67 West 3rd Street in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1946 before decamping in 1949 with her new husband, Herman Kobbe, to an art colony in New Hope, Buck’s County, Pennsylvania. As the philanthropic wings of the Carnegie and Mellon corporations cast about for a director of an arts center for Black youth, Theodore Hazlett, the president of the Mellon Trust, landed upon Burke.

Both the trusts owed their outsized wealth to Pittsburgh banking and steel magnates, Andrew Carnegie and Andrew Mellon. The trusts’ decision to establish a community-based arts center for Black youth came amidst tensions that were building to a boil following the Mellon corporation’s razing of the city’s Hill district between 1955 and 1965, displacing Black families in the city. Thanks to her residency in the state and her prominence, Burke was the perfect outsider-insider.

“Art,” she argued,” is the basis for everything,” and Burke said she was committed to “bringing art to Negro boys and girls so there can be more appreciation for living.” Despite her prominence and dedication, she often found herself caught between conservative white philanthropic impulses and proponents of Pittsburgh Black Arts Movements, who argued that Black art should be in the service of Black politics.

Still, Burke pressed on. She ensured that the center, and by extension, its students, experienced differing and competing perspectives on Black art through various collectives and networks. She also exposed her students to some of the leading Black women artists of the era: Betye Saar, Margaret Burroughs, Samella Lewis and Camille Billops.

While Burke explicitly believed art was universal, she appreciated the ways a new generation of artists were centering Blackness. And members of the Pittsburgh Black arts collective, Mbari, which included sculptor Thaddeus Mosley, were employed as instructors at the Selma Burke Art Center. Mosley and Burke would later do a two-person exhibit together in 1990 at the Three Rivers Festival in Pittsburgh. (Burke died five years later in New Hope, Pennsylvania.)

I have known African art all of my life.

Selma Burke

Burke officially retired from the Carnegie and Mellon-funded center in 1976 and the funders, rankled by the growing feminist and Black Nationalist direction of its new leadership, withdrew support in 1978. The center folded four years later though Burke’s legacy in Pittsburgh continued with the flourishing of community-based arts initiatives such as Women of Visions, which is the longest-running collective of Black women visual artists in the United States.

Though often trapped between white philanthropic demands and Black Nationalist aesthetics, Burke chose art education that instilled technique, was rooted in individual expression and remained centered in the community. For her it wasn’t a matter of either/or, but an approach that grew out of her vast experiences and made room for a diversity of Pittsburgh’s creatives.

____________________________________________________________

Tracy Sharpley-Whiting is the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Distinguished Professor of African American and Diaspora Studies, and the author of Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris Between the Two World Wars.