Out of death and darkness comes a glimpse of the Black body in heavenly form.

By Naomi Harris

Through a Pittsburgh-based artist’s vision, Black bodies are able to transcend weighted perceptions of Blackness and connect to the divine. In his series, Infinite Essence: Celestial Liberation, Mikael Owunna photographs Black models in ways that reflect the midnight sky adorned with stars.

I used fluorescent paints and ultraviolet light to illuminate Black bodies as these cosmic vessels, but then I connect them to different African myths as a way to kind of also transcend across space and time to our own ancestral origins.

On his website, Owunna says that the series is his “response to pervasive media images of Black people being shot and killed by police.”

As part of Pittsburgh’s first full acknowledgment of Juneteenth, a Texas-based holiday that celebrates the final emancipation of enslaved people, Black artists like Owunna displayed their work around the city.

From June 18 to June 30, Owunna showcased his photographs on digital billboards and kiosks in 11 different spaces including East Liberty and the airport.

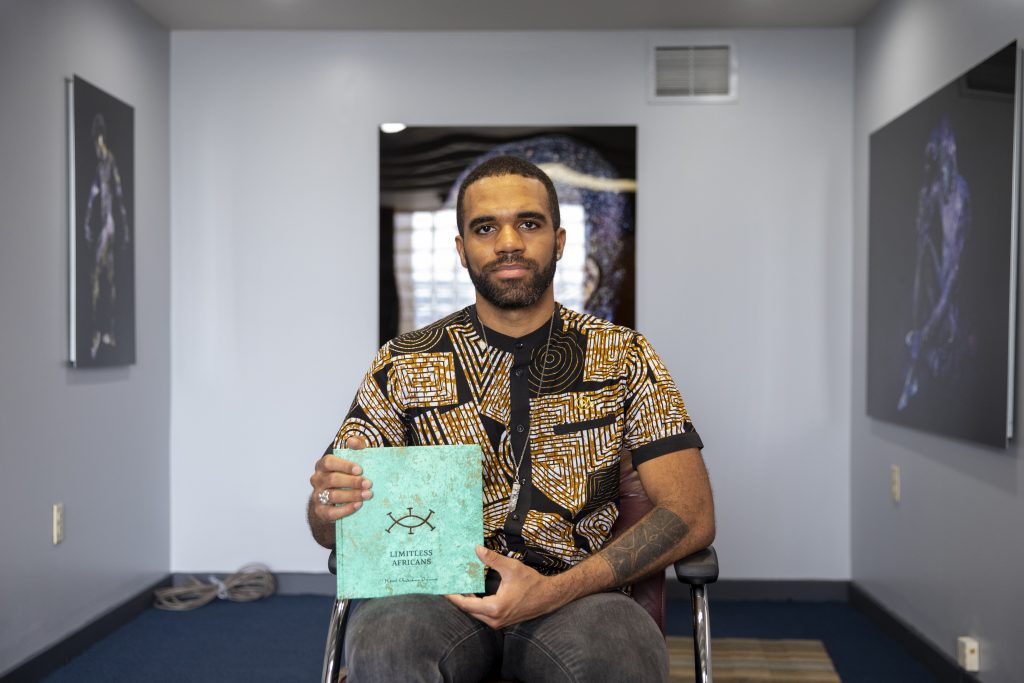

Sitting in his studio in the Hill District, the 30-year-old Nigerian and Swedish-American artist surrounds himself with his work and discusses his journey.

Whenever he picks up his camera, Owunna is always intentional.

It was the ability to envision alternative realities. So within the camera, you’re framing and you’re being really specific about what part of the world you’re capturing and how you’re capturing it. ~ Owunna

Part of the decision to place his photos across Pittsburgh instead of in a traditional gallery setting was to uplift communities with different imagery, says Larry Ossei-Mensah, the curator who worked with Owunna’s project.

Ossei-Mensah was first introduced to Owunna two years ago and after he saw the series, he knew he wanted others to see it too.

“A lot of that just comes from me believing that this work will resonate [with] a broader audience,” said Ossei-Mensah.

“I felt like this was a conversation that needed to be had publicly, particularly with regard to Black/Brown/BIPOC communities in Pittsburgh. That was why we insisted on so many different sites for the project,” he adds.

In addition to the exhibit, Orange Barrel Media also collaborated with Ossei-Mensah to host town hall discussions on police violence and the spiritual power of African cosmologies.

For Owunna, the stepping stone to this photo series shadows his work to reenvision Blackness and queer identity.

When Owunna was 15-years-old, he was outed to his family. Family visits to Nigeria for Christmas soon became a place where he had to undergo ceremonies in an attempt to “drive out the gay.”

Soon, Owunna spiraled into anxiety and depression. He says what pulled him out was his photography. A friend recommended he bring his camera for a trip abroad, and as soon as he picked it up, Owunna realized he had found his voice.

“It just really clicked for me in a way that it had never done before and so I was just really drawn to the medium,” he says. “I use it as an emotional outlet for myself.”

Owunna’s photography has transformed over the years, especially after seeing that traditional Western-style documentation of Africa focused on desolation and poverty. Once he challenged that perception and added more color and different camera angles, Owunna discovered the importance of framing—and regained his agency.

I felt really powerless. I didn’t understand my own power at the time. And I think using photography was a part of that process of reclaiming that power to control my environment because I’m able to literally frame and structure the way in which the world around me looks.

Though he found his passion in photography, Owunna had actually gone to Duke University for biomedical engineering and history. After graduation, he worked in marketing and communications and worked his photography on the side.

In 2015, he began to travel across North America, Europe and the Caribbean to capture imagery of African immigrants who were also part of the LGBTQIA+ community. For almost four years, he made sure to showcase the entire person by collaborating with models on location and clothes in the series, Limitless Africans.

The intentionality of this project also introduced him to African cosmologies, a concept that he continues to explore. In particular, Owunna wants to refute this idea that queerness was not part of historical African cultures—a pervasive perception that he hopes to change.

In fact, Owunna learned that in traditional African societies, people who were gay were the gatekeepers, or shamans, to the spirit world.

“I think from that perspective I started thinking about my work in a very different context. I started thinking about my role as a queer African as a gatekeeper, and my practice allows me to open the gates and allow people to see alternative realities,” he says.

In August 2014, Owunna was struck by the brutal murder of Mike Brown, a young Black man who was shot by police in Ferguson, Missouri. Brown’s body lay in the street for hours and soon after, images of the 18-year-old circulated in the news and on social media.

Seeing those morbid images, and then others like those of Walter Scott, Philando Castile, Tamir Rice, and Antwon Rose, Owunna says, made him want to explore ways to transcend the common connections of Black death and tragedy.

“I wanted to think about how could I transfigure Black bodies within the context of my work from being sites of death and state violence into these cosmic vessels that are connected to these ancestral mythologies that transcend all life and bring us back into another conception of what blackness means,” he says.

By 2017, Owunna decided to leave his job and fully commit to his passion, a risk he knew would be worth it.

Still, the country continues to witness countless tragedies of Black people and the police, including during the summer of 2020, where for nearly nine minutes, a Minneapolis police officer slowly killed George Floyd as he kneeled on his neck.

Owunna hopes his work displays Black people in a light not weighed down by grief and pain, adding the necessary nuance to public perception.

Blackness associated with death, destruction and violence is a really flat, socio-political construct, but by connecting them to these mythologies, we see that Blackness is this divine cosmic force that is actually the essence that produced all life.

“Blackness associated with death, destruction and violence is a really flat, socio-political construct, but by connecting them to these mythologies, we see that Blackness is this divine cosmic force that is actually the essence that produced all life,” Owunna explains.

For his Infinite Series project, Owunna built his own ultraviolet flash to properly capture the fluorescent paint decorating the models.

His connection with legacy, history and redemption is supported by the Pittsburgh arts community.

The city, Owunna said, is unique in how artists support one another. For Juneteenth, Owunna shared the spotlight with other Black artists. Pittsburgh and Allegheny County were the first in the state to make Juneteenth a legislative holiday.

Along with 1Hood Media and other organizations, Owunna curated an arts event to showcase 15 Black visual artists as a way to celebrate Juneteenth and the work of Black creatives. Throughout the city, residents were able to participate in the holiday with Black music festivals ranging from hip-hop to soul to jazz.

“I think particularly because Juneteenth is a holiday that celebrates the legacy and lineage of African Americans, I also wanted it to be something that was grounded and brought in predominantly African American artists — to be able to showcase their work,” he says.

In September, Infinite Essence goes on exhibit in North Carolina at Contemporary Art Museum Raleigh. Also in September, the artist presents his first solo exhibit in New York City at the gallery ClampArt in Chelsea. Entitled Cosmologies, the exhibit is an extension of Infinite Essence.