A coalition of social justice and civil rights groups say it begins with de-centering police from the lives of Black people

By Melba Newsome

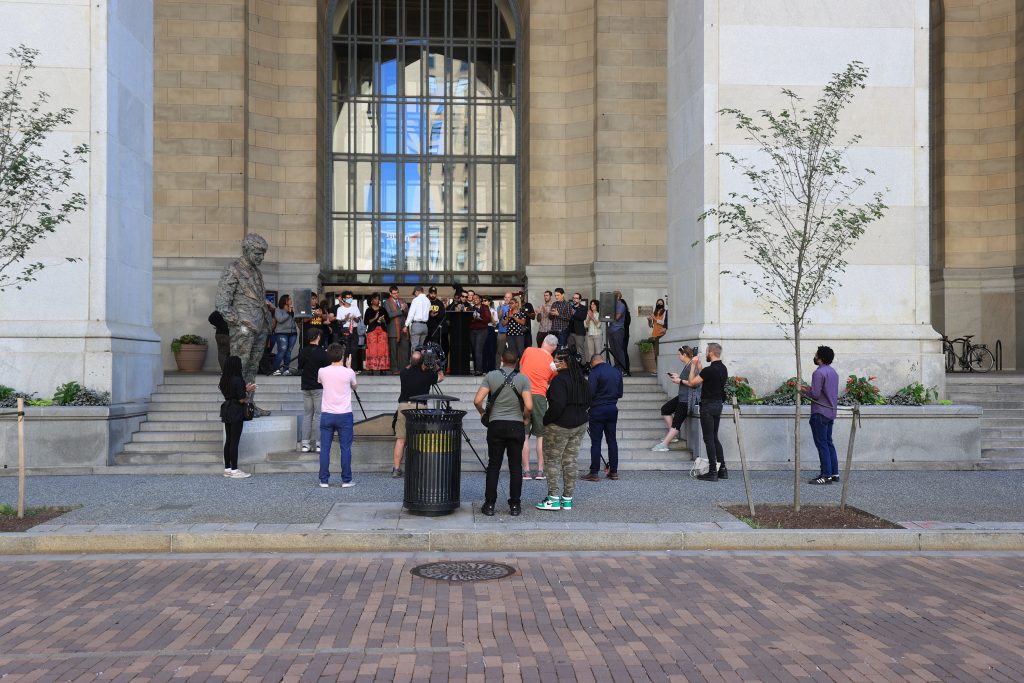

Days before Juneteenth 2021, the Coalition to Re-imagine Public Safety, a cross-section of local artists, activists and community organizers, held a press conference on the steps of the Pittsburgh City-County Building to unveil its blueprint for ending police violence against Blacks in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. The timing of their “community vision ” was not lost on them. Around the nation, elected officials (from President Biden to Congress to city mayors) continue to decry the idea of defunding the police—even as they give lip service to police reform, racial justice and equity and prepare to celebrate the first national Juneteenth holiday.

But long before Juneteenth or “Emancipation Day” gained mainstream attention, Michelle Kenney knew all about the day Union troops told enslaved people in Texas that the Civil War had ended and they were free. Her father was a student of Black history who routinely challenged conventional tropes such as Columbus “discovering” America. But tragically, three years ago, Juneteenth took on a different, devastating significance.

On June 19, 2018, after lazing around the house to escape the summer heat, Antwon Rose II ventured outside for the first time in days. Michelle Kenney had last heard from her son at around 6 p.m. and when she tried reaching him later with no response, she began to worry. She called her daughter, Kyra, and said, “Call your brother. He’s not answering.” It wasn’t like Antwon to let her texts and calls go unanswered.

Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

When Kenney went out of the house, she heard someone say that a 12-year-old had been shot and killed in East Pittsburgh. Kenney’s worry turned to panic. Even though Antwon was 17 and didn’t hang out in East Pittsburgh, she knew in her soul it was her son they were talking about.

As Kenney made her way to the scene of the shooting, she ran into police who refused to give her any information on the victim or what happened. Finally, an officer she knew from the neighborhood said he didn’t think it was Antwon but directed her to McKeesport Hospital to find out.

When I got to McKeesport, rather than the man telling me if it was my son, he’s asking me what Antwon had in his pocket, how much money he had on him, what he did that day, what he had on and all that other stuff. The way they treated me and the circles they ran me around in that night. ~Michelle Kenney

It took hours for Kenney to learn that Antwon was, in fact, the young man who’d been shot and killed and hours longer to discover that she had joined a sorority no one wants to—mothers of Black children killed by police.

Policing in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County

The history of policing in Pittsburgh and Allegheny County is littered with injustices against Black people. The National Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) was founded in Pittsburgh in 1915 to advocate for better working conditions for police. The union today has a reputation for racist political advocacy and bears responsibility for many of policing’s problems: from protecting its members from accountability to preventing meaningful oversight and reform.

One of the most high-profile deaths at the hands of Pittsburgh police happened 25 years earlier and bears an eerie similarity to the killing of George Floyd.

On October 12, 1995, Jonny Gammage, 31, was driving a Jaguar that belonged to his cousin, Pittsburgh Steeler Ray Seals, when Brentwood police pulled him over on the pretext of an expired Florida registration. Within minutes, five officers wrestled Gammage to the ground face down, hit him with flashlights, and one sat on his legs while another pinned his upper body to the ground. Seven minutes later, he was dead.

Gammage’s death was ruled a homicide by “positional asphyxia.” In other words, like Eric Garner and George Floyd, he couldn’t breathe. Three officers were charged with involuntary manslaughter. After two mistrials, prosecutors dismissed the cases against two officers; an all-white jury acquitted the third. The next year, two more Black men died in police custody.

These high-profile civil rights abuses led the US Justice Department to enact the country’s first consent decree in April 1997, which outlined steps to improve police conduct. The department agreed to track officers accused of misconduct or battery; officers were required to document more precisely why they stopped and questioned people as well as provide more justification for the use of force. But once the consent decree ended five years later, the pattern of mistreatment and abuse resumed.

- In 2010, three undercover officers arrested and beat 18-year-old Jordan Miles because they claimed they saw a gun. Miles said he thought he was being robbed and ran; Black residents were enraged by images of the teen’s swollen face and wounds in his scalp where police had torn out his dreadlocks.

- In 2012, officers shot and paralyzed 19-year-old Leon Ford during a traffic stop because police said they thought he was reaching for a gun.

- In 2015, the Pittsburgh police department settled an ACLU lawsuit for discriminating against Black applicants.

- In 2017, Sgt. Stephen Matakovich was sentenced to prison after he was captured on video beating a teenager at a high school football game.

Antwon’s Last Night

Shortly before 9 p.m. on June 19, 2018, Michael Rosfeld was on patrol in East Pittsburgh when he spotted a light-colored Chevy Cruze that was suspected in a drive-by shooting in North Braddock minutes earlier. Rosfeld made a traffic stop and ordered Antwon, the driver, and the third occupant, 17-year-old Zaijuan Hester, out of the car. One witness said Rosfeld pointed a gun at Antwon while at least one of his hands was up. Antwon then turned and ran and Rosfeld opened fire.

“It was like [Rosfeld] was taking target practice out on this young man’s back. He didn’t flinch. He didn’t say, ‘Stop running.’ He didn’t say anything,” a 23-year-old who captured the shooting on video told CNN.

A witness described Rosfeld as ‘hyperventilating and panicking’ and saying, “I don’t know why I shot him. I don’t know why I fired,” while other officers consoled him.

“Rather than render aid to Antwon, they went searching for the other suspects and left my son facedown in the dirt to bleed to death,” says Kenney. “They cuffed him until the EMT arrived.”

That night, police never told Kenney that her son was killed by a police officer. It took days to learn that Rosfeld, the 30-year-old East Pittsburgh cop who’d killed her son, had been on the job for only three weeks and was sworn in just two hours earlier. Weeks passed before she learned that Rosfeld earned $15 an hour with no benefits and had been fired from his job with the University of Pittsburgh Police just six months earlier.

“My teenager took longer to get his driver’s license than the amount of time it would take for him to become a police officer,” says Kenney.

From Freedom Corner to George Floyd

Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

Video of the shooting triggered days of protests throughout Pittsburgh, including a late-night, mile-long march from Freedom Corner to the Allegheny County Courthouse that shut down traffic.

A week after the shooting, Rosfeld was arrested and charged with criminal homicide.

Looking back on the night of her son’s death, Kenney understands why police interrogated her about her son before confirming his death: they were building a case to justify the shooting.

When Rosfeld went on trial in March, it felt as if her son was the one being tried and, like many other unarmed Black men killed by police, posthumously criminalized.

Kenney wanted folks to know that Antwon was more than a name on a police blotter, describing him as a kind, funny kid who volunteered in the community, loved basketball and could ski and snowboard. Antwon played saxophone and guitar, was an honor student who excelled at math and science, and had already been accepted to Indiana University of Pennsylvania where he planned to study chemical engineering.

One question Kenney had to repeatedly answer for others and herself: why did Antwon run?

I don’t care what kind of criminal they tried to make him, my son was a cry baby, a mama’s boy. Antwon may have been afraid of the police but he was definitely afraid of getting caught and me having to show up. I watched grown men run. So, it amazes me when people say, ‘Why does a 17-year-old run?’ Do you stand there and take the risk of being assaulted, charged, lied on … or do you run and get shot in the back three times? ~Michelle Kenney

Days before the trial began, Antwon’s friend Zaijuan pled guilty to three counts of aggravated assault and four firearms charges. During the hearing in which he was sentenced to 6-22 years in prison, he also took responsibility for Antwon’s death. “I am deeply sorry for my actions because my actions cost my friend his life,” he told the court. “I haven’t been the same since.”

But it was Rosfeld who would stand trial for Antwon’s murder. Convicting an officer for killing someone while on duty is extremely rare. Police investigations usually conclude that their officers acted appropriately, and prosecutors are often reluctant to bring charges in the first place because they must work closely with the police. Furthermore, a guilty verdict almost always hinges on whether the cop is able to convince a jury he opened fire to prevent death or injury to himself or others.

When the four-day trial concluded on March 22, 2019, the Rosfeld jurors (which included three Black people) deliberated for just four hours before acquitting Rosfeld of first-degree murder, second-degree murder, voluntary manslaughter and involuntary manslaughter.

“Not one day from the time that Antwon was murdered until today did I ever think that that man was going to jail,” says Kenney. “The DA in this county had never prosecuted an officer, let alone for murder. He couldn’t escape this because Antwon was shot three times in the back, but it was never about Antwon.”

Shortly after the verdict was announced at around 9:00 p.m, protests began outside the Allegheny County Courthouse and continued through the summer of 2019.

Most Livable City for Whom?

By the time of the May 25, 2020 George Floyd killing, Pittsburgh activists had been in the streets consistently for two years. But the Black Lives Matter protests sparked by Floyd’s murder were something different, says Jasiri X, co-founder and CEO of 1 Hood Media*, which served as co-convener of the Coalition to Re-imagine Public Safety.

The first George Floyd protest was more people than I’d ever seen on the streets of Pittsburgh. Two police cars got set on fire and about 50 people were arrested. It was chaotic, to say the least. ~Jasiri X

What began as a peaceful march of about a thousand on the afternoon of June 1 ended when police in riot gear chased, arrested, tear-gassed and shot protesters with rubber bullets. The June 2020 protests in Pittsburgh echoed the largely peaceful justice for George Floyd marches across the US that was also met with police violence. Pittsburgh Police justified the use of force by alleging that protesters threw bricks. They initially denied using tear gas, a claim they later walked back.

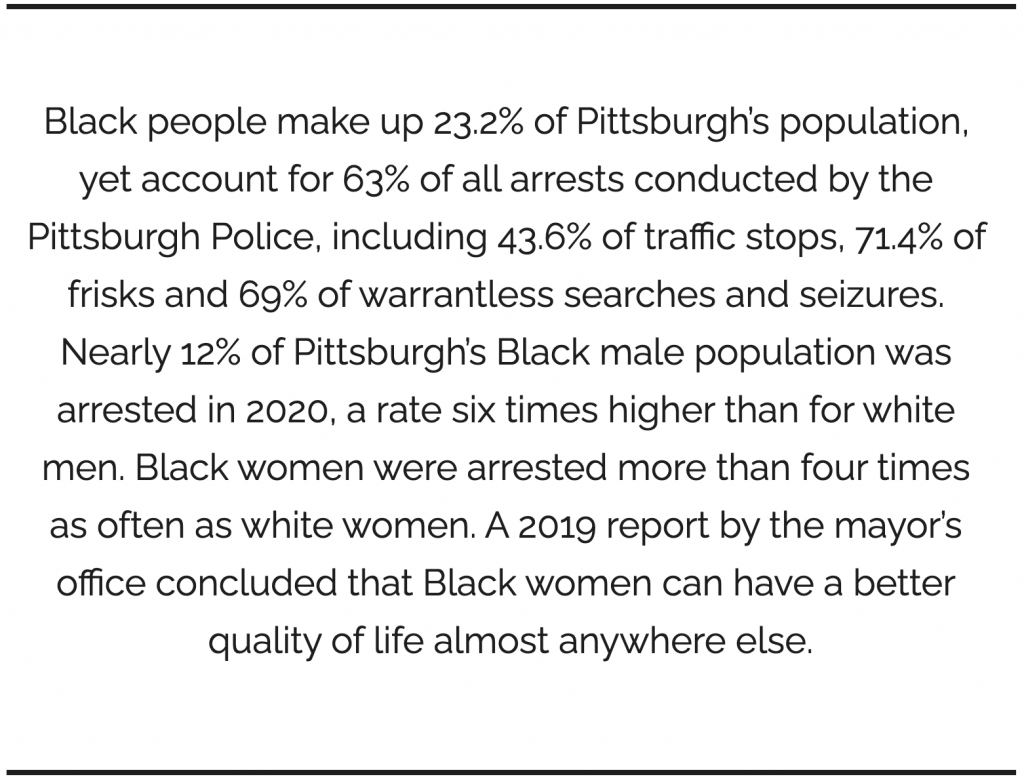

Since The Economist magazine ranked Pittsburgh several times as the nation’s “most livable” city in the mid-2000s, the moniker has stuck. But most livable for whom? Certainly not for the many Black people who find it an inhospitable place to maintain their families and thrive. This is particularly true when it comes to the Black community’s interactions with police.

Brandi Fisher formed the Alliance for Police Accountability (APA) in March 2010 after 18-year-old Jordan Miles was assaulted and brutally beaten by three undercover cops. “Before that, I was just a mom on the couch,” she says. “I had never voted before in my life. I was just a single mom with two kids, teaching Sunday school. I saw this on the news and that’s what brought me off the couch.”

Since then, APA has been fighting for policy change and advocating for accountability and equity in the criminal legal system, education, transportation and housing. APA was instrumental in ensuring the Woodland Hills School District removed police officers from schools in 2018 after a two-year phase-out.

Following the Black Lives Matter demonstrations last summer, Mayor Bill Peduto promised an independent investigation of police conduct and asked Fisher to join the mayor’s task force on police reform, which was asked to generate recommendations. She quickly became disillusioned with what she saw as posturing and resigned.

“Let’s just say that this was just a political way to have people calm down and give an appearance of trying to make change,” she says. “I felt like this was a waste of time and that this Mayor’s office does not want real change, but he’s doing the political thing.”

De-Centering the Police from our Lives

Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

Fisher and Jasiri X had worked together on different organizing campaigns for more than a decade. As fall approached, they sought a way to channel the energy from the summer protests into more sustained action. They’d seen things like cuts to the police budget in Seattle; ending qualified immunity for officers in New York City and getting healthcare professionals instead of police to show up for mental health calls in Denver.

If these cities could offer a new vision for keeping Black people safe, why not Pittsburgh? The Coalition to Reimagine Public Safety was born.

Jasiri X and Fisher (through their organizations, 1 Hood Media and APA, as conveners) received funding support from The Pittsburgh Foundation and the Staunton Farm Foundation to design a community vision of public safety.

They organized a brainstorming session with local activists and created a steering committee that included Michelle Kenney, Antwon’s mother, and Leon Ford—now 28 years old, who was shot by police nine years before and has become a leading voice in Pittsburgh for changing the relationship between the community and police.

“This really came together around October or November of 2020,” says Jasiri X. “We said, ‘Let’s have victims of police violence at the table and see if we can pull this off.’”

Unlike the Mayor’s task force or another one in 2020 led by Allegheny County, the Coalition maintains that people most directly impacted by police violence should be centered in any serious call for reimagining public safety—Black folks, families of victims, activists who participated in protests against police violence, and practitioners who run independent organizations doing work on the ground in the region.

Justin Laing, who has worked in Pittsburgh philanthropy for years, especially advancing the importance of Black-led organizations in the fight against white supremacy, chaired the steering committee. Allyce Pinchback-Johnson, a long time Pittsburgh educator, community organizer, and organizational consultant, served as project manager, and University of West Virginia sociology professor Jesse Wozniak, author of Policing Iraq: Legitimacy, Democracy and Empire in a Developing State, rounded out the steering committee as the lead writer for the report.

The Coalition jump-started its work with a town hall meeting to hear from national organizations that have shown success in advancing new approaches to policing in their own spaces. Over several months, a general committee of local artists, academics and community organizers (including Prevention Point Pittsburgh, Coalition of Predictive Policing (CAPP), Abolitionist Law Center (ALC), Take Action Mon Valley) met periodically and reported back to the steering committee. The effort also built-in ways for the community to add its voices and provide feedback, such as with virtual town hall meetings, breakout sessions and even an open working document that anyone involved could access and contribute to.

The fact that you have first conveners and then they broaden out to a steering committee, and they broaden out to a coalition, and then they broaden out to a town hall and it broadens out to national stakeholders [makes it] probably much more representative than what the state generated. ~Justin Laing

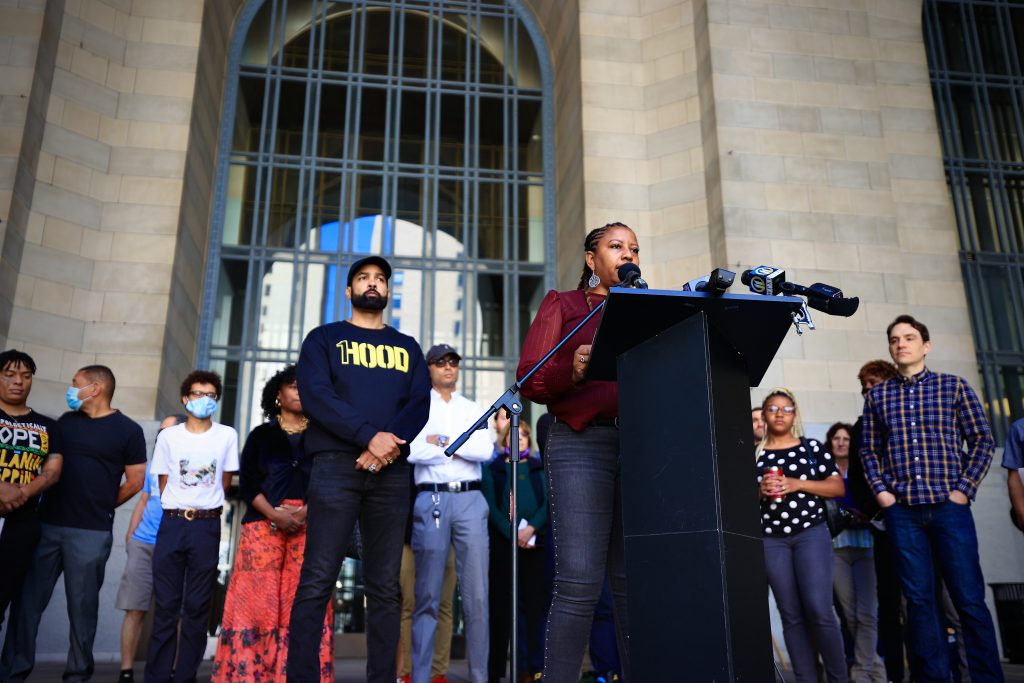

Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

Jasiri X agrees. “This was a first of its kind, community-led process in Pittsburgh that produced a document which says, this is what we want public safety to look like going forward.”

The community vision puts emphasis on non-police service, community care centers as safe, trusted spaces; an emergency call system that doesn’t involve police; and holistic responses to problems like housing, food scarcity and healthcare.

Pinchback-Johnson put it this way: “What does it look like for there to be a centralized entity that instead of calling 911, you call a different number and make sure that if a person is experiencing a mental health crisis, somebody is coming who has mental health training to support that person? What does it look like for community-based centers to pop up where people can go in and get some of their needs met? What does it look like for drug use to be decriminalized? What does it look like for big systemic change to happen so that folks do not have to live in abject poverty that then causes them to make decisions for survival that leads them into the criminal justice system or to their graves?”

Building on the research and previous reports by ALC and Policing in Allegheny County (PAC), the vision also calls for shifting money from police budgets to funding measures that will improve community health and safety through organizations that work with people experiencing homelessness, substance use disorder, mental health issues and/or community violence, including domestic abuse.

Alice Bell is the overdose prevention project coordinator for Prevention Point Pittsburgh, a harm reduction non-profit that has operated a syringe exchange service in Allegheny County since 1995. “One of the most detrimental things for people who use drugs is an interaction with law enforcement,” says Paul. “There’s never once been a situation where police involvement seemed helpful. We know from our experience, drug use is not something that necessitates police involvement.”

A common myth is that more policing equals more safety but that maxim breaks down quickly when applied to policing Black and brown people, who are often the victims of police harassment and abuse. The rate of fatal police shootings of unarmed Black people in the US is more than triple that of whites, according to research in the Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. Despite this public health crisis, the city of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County continue to increase spending on the very organizations that perpetuate systemic racism and threaten Black lives—the police.

According to public salary information, two of the highest-paid Pittsburgh police officers had a history of disciplinary infractions including wrongful arrests, abuse and excessive force dating back nearly two decades. Paul Abel Jr. earned $156,106 in total compensation before being fired last December after making two highly questionable arrests in the span of six weeks. In 2015, the year before Stephen Matakovich was charged and sentenced to 27 months in federal prison for punching a teenager at Heinz Field, he earned $190,644 and clocked in as the seventh-highest paid city employee.

Photo Credit: Emmai Alaquiva

The Beginning of Accountability?

For too long, transparency and accountability have not been a part of policing but there are signs of change.

The East Pittsburgh borough council voted unanimously to dissolve its police force after the Antwon Rose shooting (state police have patrolled the borough since Dec. 1, 2018). The borough council appointed Markus Adams, a 54-year-old Black man, to serve out the term of East Pittsburgh Mayor Louis Payne, who resigned in January 2021 after serving for 23 years.

State Senator Ed Gainey, who marched with protesters after Rose’s death, defeated incumbent mayor Bill Peduto in the Democratic primary in May and is highly expected to become the city’s next mayor. Electing the first Black mayor of Pittsburgh is a culmination of a decade of work and a wake-up call to politicians that Black voters can’t be taken for granted.

Pinchback-Johnson says the community vision was phase one of the Coalition’s work. Phase two requires an even bigger step.

“What’s next is buy-in to actualize the recommendations in the report, to have elected officials and other important decision-makers get to this vision where public safety is not about armed police officers intervening when people experience the crises that in a lot of ways have been caused by this system.”

Click here to view full Coalition to Reimagine Public Safety press conference video.

Click here to view and download the report Reimagining Public Safety in Allegheny County: A Community Vision for Lasting Health and Safety.

Melba Newsome is an award-winning freelance journalist who frequently writes about health, education and social justice.

*Editor’s Note: 1Hood Media is the publisher of BlackPittsburgh.com.